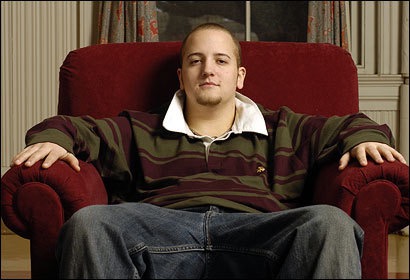

Mt. Holyoke junior Kevin Murphy is one of a handful of transgender students changing the face -- and the soul, some say -- of elite women's colleges.

THERE’S A BATTLE BREWING AT THE SEVEN SISTERS OVER THE GROWING POPULATION OF TRANSGENDER STUDENTS. THE QUESTION AT ITS COREL WHAT KIND OF WOMEN’S COLLEGE AWARDS DIPLOMAS TO MEN?

By Adrian Brune | April 8, 2007

Though born a girl, raised a girl, and now attending a women’s college, Isaiah Bartlett didn’t feel quite right being female. Old pictures show a very feminine, rosy-cheeked Allison Bartlett with chin-length dark brown hair. Yet every time her mother coaxed her into a dress for one of those photographs, Allison’s skin would crawl and her mind would race with insecurities. Even coming out as a butch lesbian in her freshman year at Mt. Holyoke College – and getting rid of those dresses for good – didn’t seem to solve the problem.

Not long after Allison enrolled, in the fall of 2005, she shaved most of her hair into a mohawk and picked up a few pairs of boxer shorts. Soon she started binding her breasts with an Ace bandage every day before going out. After a year of struggling in school and a semester off to sort out her emotions, the popular 20-year-old psychology major returned to school and went to a talk by fellow student Kevin Murphy. Then things began to make sense. Allison realized that though she was a biological woman, she wanted nothing more than to be a man. She adopted the name Isaiah. “When I heard Kevin’s story, his talk about struggling with coming out as a lesbian, then realizing that he really wanted to be a man, I felt as if he was telling bits of my own story,” Bartlett says one October afternoon in his room in Mt. Holyoke’s Buckland Hall dormitory, just before a friend comes barreling up in a robe and a green face mask to offer a quick hug and some dish. “Soon after, I came out as a transman.”

This is the latest subculture to emerge at the elite women’s colleges in the Northeast known as the Seven Sisters – young women, some still teenagers, who, like Bartlett, are exploring the possibility of growing up to be men. And it’s creating a social upheaval at these historically all-female enclaves as they wrestle with what to do about all this gender bending.

The Seven Sisters colleges were founded in the 19th century, and famous graduates have ranged from anthropologist Margaret Mead (Barnard) to actresses Stockard Channing (Radcliffe) and Meryl Streep (Vassar) to Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton (Wellesley). Vassar started accepting male students in 1969, and Radcliffe officially merged with Harvard College in 1999, leaving just five sisters – Mt. Holyoke, Bryn Mawr, Smith, Barnard, and Wellesley.

But the same empowerment and opportunity for self-discovery that an all-female school provides may also make survival as single-sex institutions that much harder for the remaining sisters. After all, the real challenge that transmen are forcing women’s colleges to face is an ideological one: Is it still a women’s college when some students who were female as freshmen are male by graduation day?

The term “transman” is a relatively new one. It originates from “transgender,” which generally describes people who feel that the gender they were born into is at odds with their true identity. Coined in the late 1970s, transgender is now often used in place of “transsexual,” which describes a person who has had sex reassignment surgery or who lives as a member of the opposite sex. Most transmen begin their transition with masculine dress, adopting the pronoun “he,” and taking on a male name. After counseling, some transmen start taking the hormone testosterone, known in the community as “T,” which deepens the voice, causes facial hair to grow, enlarges the clitoris, and reduces breast size. If he decides to go further, a transman may undergo a double mastectomy, hysterectomy, and ovary removal. The final frontier is penis construction surgery.

From a medical point of view, Isaiah Bartlett’s story reflects the classic traits of gender identity disorder as defined in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” the bible of the mental health professions. At the same time, while no one knows exactly how common it is, advocates and many professionals who work with the trans population believe transgender people should be reclassified, because gender variation is normal across the human spectrum.

It does seem that most transmen start to feel male at a young age. A study conducted two years ago by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Pennsylvania State University asked transmen, transwomen, “genderqueers” – who consider themselves beyond or between genders – and people with other gender-diverse identities about their experiences. Roughly 3,500 people responded to the survey, sent to transgender support groups throughout the country and to self-identified transgender individuals found online. Of the 807 respondents who were female at birth but who now identify as male, transgender, or “other,” 86 percent said they began to question their gender identities before age 12, and all but 2 percent before 19.

In addition, researchers believe that more young people than ever before are acting on those feelings. “It used to be that transitioning was a midlife process, but the Internet has changed a lot,” says Brett-Genny Janiczek Beemyn, one of the lead researchers in the UMass-Penn State study. “With the click of a mouse, more and more young people can find others going through what they’re going through and have a stronger sense of themselves at a younger age.” Beemyn, who also directs the UMass-Amherst Stonewall Center, an educational resource center for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students at the school, believes that in the coming years the number of young people who are “out” as transgender will only grow. Advocates think that’s a good thing: A number of studies have found that the earlier an individual undergoes sex reassignment, beginning with hormones, the easier it is for that person to pass as someone of their transitioned gender, and that passing is key to a transitioned person’s long-term happiness.

Though a successful transition can certainly be a liberating experience, the growing transman population at all-women’s colleges has created some unique problems, too. While both Mt. Holyoke, in South Hadley, and its rival school, Smith College in Northampton, cultivate what transgender students say is an open and accepting environment that allows them to find their true selves – including their gender identities – there are new rivalries developing. “No parent is surprised anymore when their daughter goes to an all-women’s college and then comes out as a lesbian,” says Kevin Murphy, the 21-year-old junior whose talk inspired Isaiah Bartlett. “But once you get into this, within the community, there’s a lot of competition. Who goes on T first. Who is taking more T. Who gets top surgery first.”

Sitting in a dimly lit bar after playing a club hockey match against Smith – club teams aren’t covered by the NCAA regulations that ban college players from taking testosterone – Murphy is practically indistinguishable from a very small, fairly handsome young man. He has deep brown eyes and, having been on T for the past two years, an even deeper voice, as well as a beard that is filling in nicely. A year ago, he used his own money to pay for a double mastectomy. Today he strolls into the bar, flashes his ID, and sits down to a Corona without a hesitating glance from anyone, including the bartender, who might have noticed that Murphy’s driver’s license still lists him as female – something he can legally change in Massachusetts, thanks to his surgery. Yet for all his confidence, Murphy, who is majoring in psychology and religion, is still figuring things out. “When I go out with my friends, I’m the guy in the group, and when I go out with their boyfriends, I’m the most feminine guy,” he says. “I’m really trying to form friendships with biological men because I want to be accepted, and I was never allowed to when I was younger.”

Beginning in high school, when Murphy came out as gay, a fairly typical transgender progression followed: dressing in drag, adopting a male haircut, and breast-binding. Kevin was still Caitlin when he enrolled at Mt. Holyoke in 2003. After about two years, Murphy decided to make the leap. “I wanted to be a guy,” he says. So Caitlin started taking T, legally changed her name, and began looking for surgeons. Murphy insists he will never regret his decision to become male, though the process hasn’t been entirely easy. “I cried the day after I woke up and found my breasts gone,” he says. “With each stage, I feel like I’ve been losing my lesbian identity, and that’s hard to give up.”

Therapists, doctors, and college administrators are concerned about students who decide to transition based on what sometimes seems to be shaky logic: growing pains such as insecurity or peer pressure, childhood trauma, depression, or even just the need to rebel. They tend to be cautious about their clients’ transitions, but many counselors ultimately feel that even young adults should be able to make their own decisions. “Of course, any compassionate therapist might be concerned about a young person making such a permanent decision. ‘What if this person could make a mistake? What if I make the wrong decision in giving the OK for this person to transition?’ ” says Arlene Istar Lev, a family therapist and adjunct professor of social welfare at the State University of New York at Albany who specializes in transgender issues. “But here’s the catch: We know that a certain percentage of the population is transgender, and we know the research on transitioning and age. At this point, we have no evidence of any young people regretting these decisions. And the other thing: We all have to live with decisions. Young people drop out of high school, even when counselors say, ‘Don’t do that.’ People get pregnant and have babies or get abortions. All you can do is give the best assessment at the time.”

A Smith School of Social Work student, Shannon Sennott, has started a nonprofit called Translate, to provide training and seminars for women’s colleges. Sennott believes that the schools should offer hormone counseling and advocacy as transgender students make crucial decisions about their lives. “Any person that age needs direction, and my concern is that they’re not receiving it,” Sennott says. “Someone needs to say, ‘OK, you want to be a transman, let’s discuss these options.’ Or, ‘OK, you want to remain genderqueer and use female pronouns the rest of your life, that’s just great, too.’ ”

It’s not that there aren’t any resources for students. At Mt. Holyoke, there’s True Colors, a student organization that runs a community center; the group arranges movie nights, mixers, and panel discussions and seminars for lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students on subjects such as coming out as transgender at work. There is also a designated adviser for transgender students on campus, an associate director of residential life who is a gay man. At Smith, similar services and groups are available.

But at Bryn Mawr College in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, the transgender community remains so nascent, there are few resources. “There are 1,300 [undergrad] students here. It’s a tiny population – I know all of the trans students,” says Lindsay Gold, 21, who guesses that the campus’s transman population is between six and 12 students. The would-be senior majoring in computer science left school in December because she “wasn’t feeling in the academic spirit,” she says. Gold is now living in an apartment near campus and trying to sort out two big hurdles: finishing college and being transgender. “Everyone is accepting, but there are no resources. People come to me asking where they can go to get help.” In an e-mail, assistant dean Christopher MacDonald-Dennis writes: “This is an issue we are only now beginning to talk about. . . . We realize that our other sisters have been dealing with this, so we are looking to them to help us be as supportive as we can.”

The trans population at Smith has seen the most public attention, and probably the most public debate, too. Former student Lucas Cheadle helped bring widespread attention to the issue by being profiled, along with three other transgender students, in a multipart documentary called TransGeneration that aired on the Sundance Channel in 2005. Before that, it was a major victory for trans activists on Smith’s campus when, in 2003, all references to “she” and “her” in the student constitution were changed to “the student.” Students say another fight over the pronouns used in the constitution looks to be rekindled in the coming year, and every so often, members of the trans-friendly and not-so-trans-friendly communities exchange heated words on the public website smith.dailyjolt.com. A recent anonymous posting about an annual event formerly known as Celebration of Sisterhood, renamed Celebration in 2003 – though there is debate as to why – reads: “Yeah, God forbid anyone include the word ‘sisterhood’ . . . because a handful of trans students somehow feel oppressed, despite the fact that they chose to attend a women’s college.” The reply: “Let the transphobia debate begin again.”

One first-year student who didn’t want her name, major, or hometown used for fear her views would provoke hostility from fellow students, says she has witnessed conflict offline, too. “I’ve heard some of the most liberal people – feminists and even gays and lesbians – say adverse things toward trans students at Smith,” she e-mails. “One of my friends, who is a lesbian also, expresses anger toward trans-identified students because she thinks they are giving up their womanhood. Although I do not agree with these opinions, I can see where they come from.”

Another camp worries that as the school makes room for transgender students, it will be forced to start accepting transmen who began their transition in high school and biological males making the transition to female. Or worse yet, it might, they say, become coed. Taking T and planning to transition doesn’t go with the mission of Smith College, writes Nicole, a junior who doesn’t want to share her last name or her major because she thinks her views will be thought politically incorrect.

A member of Smith’s Republican Club and editor-in-chief of its conservative newspaper, junior Samantha Lewis, 20, doesn’t mind speaking on the record. “I think it’s ironic that there are Smithies who do not want to be women, and, to be completely honest, it seems to me that it defeats the purpose of being at a women’s college.” While Nicole guesses that the trans population at Smith is 30 out of about 2,500 undergraduates, Lewis thinks that the number is at least twice as big. “The first person I met on campus was a man,” Lewis says. He said, “‘Hi, I’m Ethan, and I use male pronouns.’”

The administration paints the conflicts as healthy, lively, debate. “Questions about what it means to be a woman or a feminist are not new to the college discourse, whether at Smith or many other leading institution,” writes Maureen Mahoney, the college dean, in an e-mail. She adds that Smith recently opened a Center for Sexuality and Gender as a student resource and for years has allowed students to request the name they desire on their diplomas. “For the most part, these are issues of diversity, and diversity has clear educational benefits. As one of our student leaders noted in an address to her peers, what she learned at Smith is, great minds don’t think alike.”

No, clearly, they don’t. “The students here try very hard to be accepting of almost anything, and it’s really difficult for us to say, ‘Hey, you don’t really belong here,’” says Nicole. “It’s not a matter of discrimination or approval, it’s a question of that person’s goals and the overall goals of the university. I personally don’t think trying to pass as a man and having Smith College on your diploma gives you the chance to have a stable career. And there are those of us who are investing in Smith, and in 40 years, we want Smith to be greater as a women’s college than it is now.”

Meanwhile, back at Mt. Holyoke, Isaiah Bartlett remains in gender limbo. “Although my decision to have surgery isn’t dependent on my parents’ approval, more of a support system from them would help a lot,” he says. As far as starting testosterone, Bartlett thinks about it, but ultimately demurs. “I’m not ready to make that kind of a decision yet.” But at Bryn Mawr, Lindsay Gold can’t wait to begin to transition and started seeing a gender therapist last month. “I feel like other transmen accept or validate you based on where you stand in your transition,” Gold says. “I don’t want to be sneered at for still having a woman’s body."