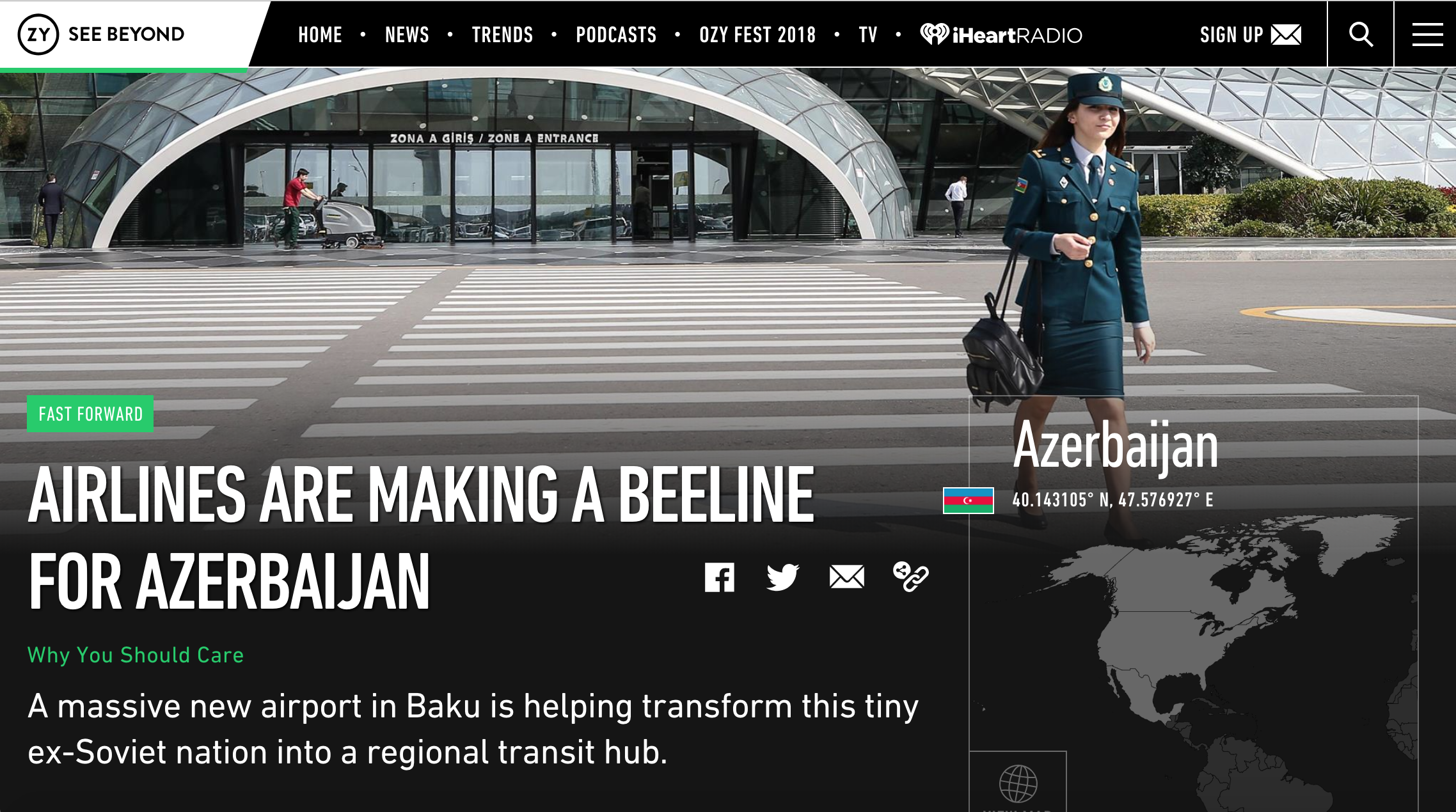

Why You Should Care

A massive new airport in Baku is helping transform this tiny ex-Soviet nation into a regional transit hub.

By Adrian Brune

THE DAILY DOSE, AUGUST 13 2018

Language teacher Tim Stuebbe had visited Georgia and Armenia before he landed at the Heydar Aliyev International Airport in Baku, Azerbaijan. He was surprised by how “developed, clean and organized it seemed.” It’s also massive, at 65,000 square meters, larger than any other airport in the Caucasus. And his response is exactly what Azerbaijan is counting on, as it attempts to emerge as a regional transportation hub.

Just seven years ago, when construction on the airport began, those dreams appeared beyond Azerbaijan’s reach. The country’s old international airport — its gateway to the world — had airlines flying little more than two routes: to Moscow’s Domododevo airport and Istanbul’s Kemal Ataturk airport. Now, in 2018, more than 30 carriers are delivering passengers to 40 destinations from Heydar Aliyev. Those numbers are expanding. Starting in March, big-name carriers such as Etihad Airways, Air Arabia, Wataniya Airways and Jazeera Airways have made direct flights from places such as Abu Dhabi or Kuwait City — even Tel Aviv — to Baku. More and more passengers are flying out from Baku as well. In 2017, Heydar Airport served 4.06 million passengers, exceeding 2016’s figure by 23 percent. In the first half of 2018, 1.96 million passengers took flights out of the airport, 14 percent more than during the same period last year.

It isn’t just foreign airlines Azerbaijan is relying on, though, to realize its ambitions. Before it rebuilt the Baku airport, it sank more money into its flagship air carrier, AZAL, taking delivery of two out of five Boeing 787 Dreamliners it had ordered and investing in several 767 freighters. More than 815,000 passengers, or 41.6 percent of the airport’s total traffic for the first half of 2018, traveled aboard AZAL, while its low-cost subsidiary, Buta, carried some 216,000 passengers. AZAL launched the country’s first flight to the Egyptian resort city of Sharm El Sheikh earlier this year.

And there’s a third prong — other than the new airport and Azerbaijan’s national airlines — to the country’s strategy. Like Iceland, another small nation 3,000 miles away that has turned itself into a successful air transport hub, Azerbaijan is also aligning the airport’s growth with a broader tourism reboot. In May, the government established the State Tourism Agency and Board (STAB), a dedicated official tourism promotion body to spread word across Central Asia about Azerbaijan’s Caspian Sea shoreline, its Caucasus Mountains and its UNESCO World Heritage Gobustan National Park. During January–April of 2018, 847,600 tourists arrived in Azerbaijan from 182 countries — 13.4 percent more compared to the same period in 2017, according to the World Economic Forum. In 2017, about 2.69 million tourists visited Azerbaijan — 20 percent more than during 2016. Most tourists came from Russia, and then Georgia and Iran. But the number of arrivals from EU member states in 2018 has increased by 12.4 percent.

For all those entering or transiting through Azerbaijan, the airport gives tourists the perception that “the Caucasus are an authentic yet easy-to-reach and comfortable destination,” according to Fuad Naghiyev, the head of STAB.

An Azerbaijan passenger plane at Vnukovo Airport during a snowstorm.SOURCE MARINA LYSTSEVA/GETTY

The month of July served as an example of just how far Azerbaijan’s international airport has come. On July 12, a British Airways Boeing 777 carrying 214 people from London to Mumbaimade an emergency landing there after the failure of its left engine. Five days later, Italian President Sergio Matarella arrived for an official visit, complete with a guard of honor and national flags all-round. And it was announced that Heydar Aliyev will receive the first flight of Turkish Airlines from the new Istanbul airport — slated to become the third largest in the world, serving 90 million people annually — later this year.

The airport’s emergence as a major transportation hub is in keeping with Azerbaijan’s desire to open up, said the country’s president, Ilham Aliyev, at a ceremony in May in which Skytrax conferred its five-star airport rating on Heydar Airport, named for his father, the third president of the country. “If you look at the building from above, the building resembles a large bird with spread-out wings,” said Aliyev. “Similarly, Azerbaijan is developing with its wings spread out wide and moving forward.”

While the airport has already changed much for Azerbaijan, there is still more it could do, say experts. In addition to the business window, human-rights groups say that unless Azerbaijan has an independent civil society and free media, an airport named for a dictator will not diversify Azerbaijan’s economy enough to democratize it. “President Aliyev’s Azerbaijan doesn’t pass the test,” says Brigitte Dufour, director of International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR). “EU leaders should make it clear that there won’t be stronger ties with Azerbaijan until the government ends the crackdown on … dissenting voices.”

Still, Heydar has brought change, including in the design zeitgeist of the country. To fill the entirety of the Heydar Airport’s passenger spaces with cutting-edge architecture and interiors, including custom-made wooden bespoke furnishings and lighting schemes, the Azerbaijani government hired Autoban, an Istanbul firm known for its stylish restaurant schemes. The various “cocoons” the firm devised — made of tactile natural materials such as wood, stone and textiles and housing an array of cafés and shops — have the effect of creating a more intimate, and secular, landscape within the massive transportation hub. “The cafés were filled with locals drinking beers and enjoying watching the World Cup,” says Stuebbe.

Now that Heydar Aliyev Airport has a foothold in the region, Oxford Economics, a consulting firm, expects the Heydar effect to further lower transport costs — particularly over longer distances — increase competition and open foreign markets to Azerbaijani exports. Ultimately, apart from generating business, human rights groups are hoping that an airport named for a dictator will nonetheless diversify Azerbaijan’s economy enough to democratize it.

In a May interview with Forbes, Naghiyev, the head of STAB, acknowledged that because the global tourism market is saturated with enticing destinations, there’s a need for Azerbaijan to make a “distinct mark in the minds of consumers.”

It already has for Stuebbe. Contrary to its Soviet past, the country he saw “was a very welcoming and easy place to arrive to,” he says. With the new airport and its expanding traction in the aviation industry, that welcome now starts from the moment a visitor lands.