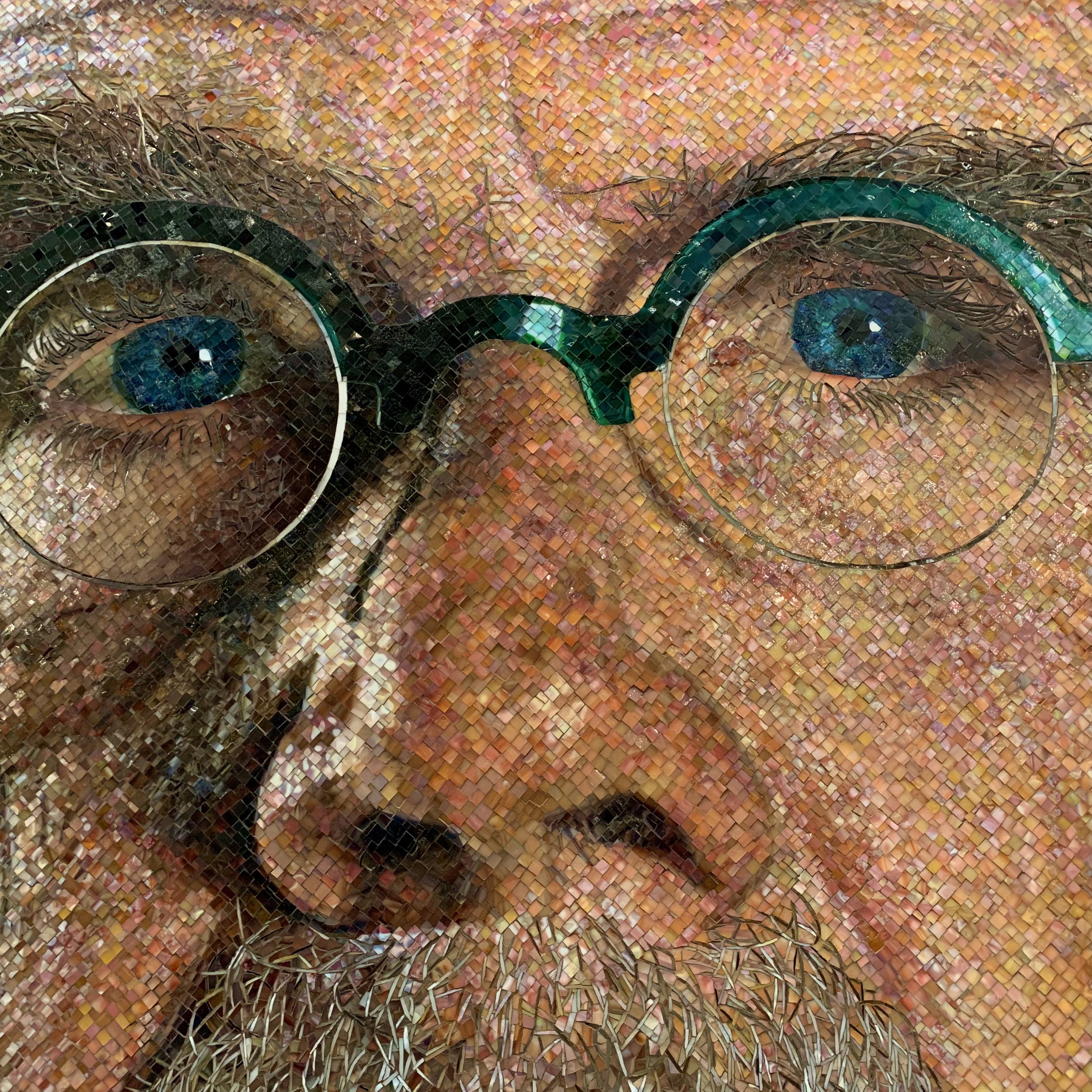

He once painted fakes to trick art galleries; now he paints them for wealthy customers

Written By: Adrian Brune

John Myatt held his breath as the bidding began in the Christie’s auction room. His drawings were selling, one by one. He had dreamed of having his work on the block since the beginning of his career. He felt a tingle of adrenaline as the paddles went up… and victory as he strolled through the city streets with a wad of money in his back pocket afterward. But the feeling didn’t last long. Eventually, Myatt started to feel empty and disappointed.

The psychic void grew as the prices that his agent, John Drewe, sought for his work went up and up. An undertaking that had begun with a straightforward 1987 magazine advertisement for “genuine fakes from £150” had grown into an elaborate, and highly remunerative, scam involving forgeries attributed to Matisse, Chagall, Ben Nicholson and more.

According to investigative journalist David Pallister, who wrote about the Myatt case for the Guardian, many psychologists and profilers classify forgers as a “peculiar breed” whose motive is not only money but recognition. “Technically adept, often with formal training and a keen sense of color and form, they have produced work, down to the singular brushstroke or cut of the clay, that rivals the originals.

“But, by definition, they have not found their own voice; they are unable to put their name to pieces of modest integrity and flair when they know that they are capable of simulating the greats. Lacking the prerequisite metropolitan social connections, they find the international art market — the galleries and auction houses of New York, London and Paris — intimidating, haughty and false… so beating the market is a challenge and a game: fraught with danger but ultimately exhilarating.”

John Myatt defied that profile. After the Christie’s auction, he told Drewe, equally accomplished at forgery — in his case of provenance and sale documents to back up the fraud — that he wanted to quit. Myatt had hit a fallow period; he tinkered with a fake of a Giacometti “Standing Nude” for weeks, unable to get the stance correct. He worried about being discovered by the people in his Staffordshire village, especially his church. So when he was busted in 1995, he didn’t run, he didn’t call a lawyer, and he didn’t deny his culpability. He simply got in the car with the Scotland Yard detectives, ready to comply. At that moment, Myatt, who turned Queen’s Evidence, promised to end his life’s work and never to paint again.

“I would not do [the fraud] again that I did when I was forty-nine,” Myatt, then sixty-nine, told the Independent in 2014. (Myatt and his wife, Rosemary, declined to comment for this piece.) “Back then I was at a particular point in life, with particular circumstances. In any other circumstances I think I would have found Drewe particularly off-putting rather than compelling. The worst part was that I’d given up the crime eighteen months before they caught me.”

Myatt believed that his forgery jig was well and truly up. But even before his and Drewe’s jail sentences began, Myatt received a request: Would he paint the family of detective sergeant Jonathan Searle, the man who’d busted him? Myatt earned £5,000. Next customers: his team of barristers, one by one, followed by more detectives of the Scotland Yard Art and Antiques Unit. Soon, Myatt had enough work to carry him through the end of 1999 and net him £18,000. “A detective said to me there’s an awful lot of police people, barristers and lawyers who were involved in this case who would love a memento,” Myatt has said.

Since then, his infamy as one of the world’s most prolific forgers has brought Myatt fame, fortune, renown and even respect. Just after his release from Brixton Prison, where he served four months of a year-long sentence, he started his own company, Genuine Fakes, which reproduces works he imagines might come from such artists as Edward Hopper and Picasso (sometimes including a cameo from Myatt’s dog Henry) and sells them for £700 and up.

In 2009, journalists Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo published Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art — a finalist for the Edgar Award for the best in mystery writing. And the UK independent company Green Eye Productions has produced Genuine Fakes, a biopic based on Myatt’s life, with Sir Derek Jacobi and Alex Kingston.

Myatt’s lucrative work as a forgery expert for the London Metropolitan Police also continues. It’s necessary: an art-world insider estimates that 10 percent of works in art museums are fakes, and the former director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas Hoving, once estimated that 40 percent of artworks on the market are forgeries. But what separates Myatt from Old Masters forger Eric Hebborn, whose memoir Drawn to Trouble came out during Myatt’s scheme, or Han van Meegeren, a connoisseur of the Dutch Golden Age who sold a counterfeited painting to Nazi Hermann Göring?

The old Myatt, the self-deriding artist of the mid-Nineties, might have said “nothing.” The thriving Myatt might say that his were never copies, but interpretations of an artist’s work. “When I paint in the style of one of the greats… Monet, Picasso, Van Gogh… I am not simply creating a copy or pale imitation of the original. Just as an actor immerses himself into a character,” Myatt has said, “I climb into the minds and lives of each artist. I adopt their techniques and search for the inspiration behind each great artist’s view of the world. Then, and only then, do I start to paint a ‘Legitimate Fake.’”

But any reader of Salisbury and Sujo’s book can tell it was Myatt’s desperation that brought him to Drewe, the master grifter. Myatt was the son of a farmer, an art school grad, failed songwriter and divorced father of two trying to support his children on the salary of a local art instructor.

Having shown some originality and talent as a student, Myatt painted mostly country landscapes, which didn’t exactly take off in the burgeoning London art scene of David Hockney and Damien Hirst. So Myatt placed that ad in the satirical monthly Private Eye, soliciting customers for his “genuine fakes” of nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings for £150, having once confected a Raoul Dufy for a friend who had admired the real thing in the home of a Marks and Spencer executive.

The ad brought a trickle of commissions and, for better or worse, delivered Dr. John Drewe. Drewe, a secondary-school dropout from Sussex whose real name was John Cockett, passed himself off as a renowned physicist and well-connected connoisseur. He wanted “a nice Matisse.”

At a drop-off spot in London’s Euston station, Myatt delivered the fake Matisse and took an order for more paintings, such as “another early twentieth-century work, this one in the style of… Paul Klee.” Drewe ingratiated himself with players in the London art scene, at the same time delving into museum archives to create provenances from artists like Georges Braque and Roger Bissière. He would ultimately use these to convince gallerists and auction houses to buy Myatt’s forgeries.

Drewe and Myatt’s ultimate downfall came from an unexpected source. Myatt had never wanted a Bentley like Drewe’s or a big house in Golders Green. He wanted to provide for his children and had been man- aging that well enough, according to Salisbury and Sujo, producing more than 200 paintings over ten years, which sold around the world for a total of about £2 million, netting Myatt about £275,000.

It still wasn’t enough for Drewe. In 1993, he left his Israeli partner, Batsheva Goudsmid, a former member of the Mossad. Goudsmid took her suspicions and a briefcase full of Drewe’s forgery kit to the police.

While the relieved Myatt cooperated, Drewe represented himself and was sentenced to six years in prison, serving two. (Drewe, who has since been convicted of at least one additional fraud, refused comment for this article.)

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the art market was booming with no fewer than 550,000 fine art lots sold via auctions throughout the world, generating a total of $13.3 billion. That’s the highest ever-recorded number of fine-art auction lots sold in one year, according to a fine art publication. Boosted by confidence in online sales after two years of limited travel, private sales at auction house like Christie’s and Phillips increased dramatically; mid-market sales, as well as resales, flourished, and buyers were optimistic about new material and expanding their collecting areas.

A booming market of any sort opens new possibilities: “It is normal in all walks of life to have fakers and scammers — [the fakers] were just part of the system,” says Peter Nahum, an English art dealer who once did business with Myatt and Drewe. Although Nahum says, “I don’t like fakers and don’t like anyone making a living from them either,” he concedes that “in the future these works will probably be sold as genuine and so the whole cycle starts again.”

In an improved economy, Nahum believes the forgery market will also improve. “They get rid of some of the (fraud) gangs and others take their place. There might be as much as 50 percent of works that are either fakes or miscatalogued. It is the expert’s job to expose and avoid all of them.”

Nahum may be right. Myatt is seemingly everywhere selling his fakes: Sky’s Fame in the Frame — a special in which Myatt painted six celebrity sitters into a famous painting — as well as Virgin Virtuosos, several exhibitions around England, including both fakes and original work and now the movie. Does it bother him that more people still want the fakes? “That’s the nature of the beast, and there’s no escape,” Myatt said. “Many fakers have no voice of their own at all. I have paintings I want to paint. I’m not sitting there with painter’s block.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2025 World edition.