On a chilly February morning – the after-effects of a surprising and significant rain shower – in Bismayah City, a small Baghdad suburb with low-slung Soviet-style block housing, a team of four girls proudly decked out in Iraqi team jerseys over long-sleeve shirts and leggings, ride hard on Turkish-made bicycles. Back and forth, around in circles, they pump hard and coast, repeating their loops as their coach Samed barks commands in Arabic from 20 or so metres away. Occasionally, a car or a taxi passes. Otherwise, the young girls – Lanyah, Sarmad, Rania and Malek – rode relatively unhindered, possibly for the first time all week.

The manager of the Iraqi National Women’s Cycling team, Basma Ayad, remembers those relatively carefree riding days, as well – back before the bombs started to fall. The daughter of secular civil servants under then-President Saddam Hussein, she would race the girls and boys in her neighbourhood and try out all the new bikes arriving in Iraq: mountain, hybrid, aluminium – basically whatever had two wheels and a seat. “I felt so free when I cycled,” Ayad said over cappuccino and cake at The Grinders, one of Baghdad’s new coffee shops springing up all over the resurgent city. “Even if it was just in our neighbourhood. We could see into the distance and imagine a better future.” While attending a local university in 2003, she met the like-minded Sura Alatar, also the daughter of non-religious, sports-minded parents (Alatar’s brother is former football player and coach at the University of Baghdad). Together they formed an amateur team and began com- peting against other clubs and universities.

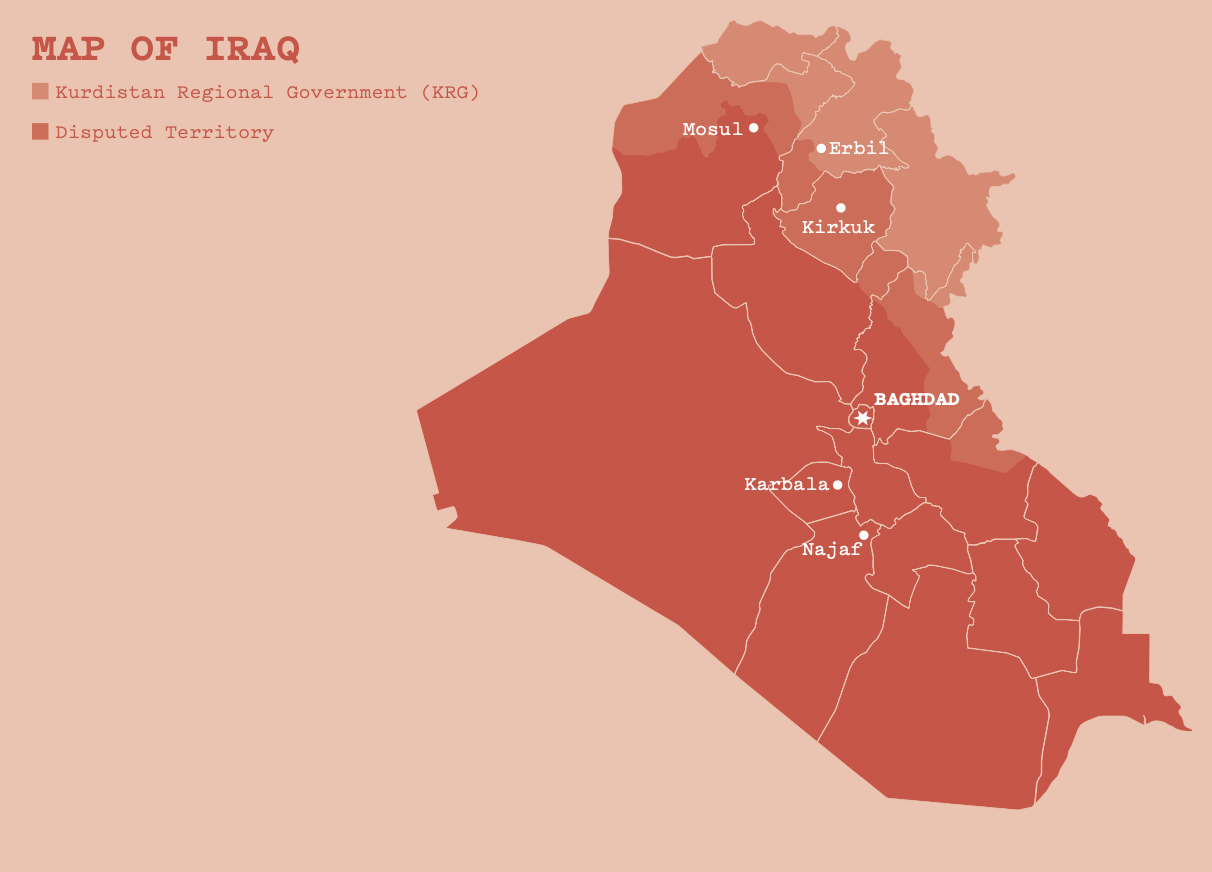

But unbeknown to most young Iraqis who thought only of Hussein in passing, the dictator kept pushing the buttons of the George W. Bush administration after the September 11, 2001 attack. Two years later, the USA had its excuse: yellowcake uranium and Weapons of Mass Destruction. For the first six months, as 130,000 troops made their way from Basrah to Baghdad, “we were not able to even leave our houses,” Ayad says. Safety was the priority. Buildings would blow up and friends would disinte- grate in the rubble. Restive men and women would have their houses raided or get gunned down around them. From the outset, the USA couldn’t find legitimate leaders to take charge of the new Iraq – some had been killed by the regime; many had gone into exile; and the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA)’s de-Baathification policy removed everyone with any civil service knowhow. The US military had already categorised Iraqis on three-by-five-inch cards as good guy (pro-America or Kurd), bad guy (anti-America or Arab) and other (students, mothers, children). “Good Iraqis received full support or money and respect. Bad guys got wrath: kill or capture,” according to Emma Sky, a British diplomat assigned to Iraq during the invasion. And the joke among the Americans about the CPA? Can’t Provide Anything.

Yet Ayad and Alatar and their nascent team kept pressing on, inventing races and raising money to travel to regional events in Jordan, Syria and North Africa, and compete. “I was an adolescent at this time and I didn’t understand really what was happening. Kids, they want to play, they want to cycle. I wanted to continue on my team,” said Ayad, a slender, dark-eyed modern mother of three. “After that, we tried to get on. We continued our studies, we took our cycles to different places in our neighbourhoods, in our little cities and we said, let’s make a cycle, let’s do it ourselves anyway.” Little did they know that they had started their own rebellion, which would later become Iraq’s first national women’s cycling team.

Known as the Iron Horse, the first bicycle started climbing Iraq’s roads in 1906 – during the Ottoman Empire’s (1534-1920) waning years. While the Europeans figured out how to make their two-wheeled mounts go faster, Iraqis used them mostly for basic transportation, especially in areas where fuel wasn’t available for motorcycles. Following the British Invasion, the fall of the Ottomans, the Middle East division and the installation of King Faisal II – the UK-installed local representative of the powerful Hashemite dynasty – all of Iraq’s provinces had thriving female athletic scenes, with active clubs in different sports. But although men’s cycling took off, women’s cycling stalled. Many families still held old-fashioned beliefs about cycling and virginity, as well as women’s freedoms, and patriarchal government officials prioritised men's clubs. Yet, despite the years of royal overthrows, revolutions and Ba’ath party domination, sport and cycling continued in Iraq, as the nascent country still dreamed – quixotically or not – of hosting the Olympics.

In 1980, Saddam provoked the Iran-Iraq War, however, and halted sport development for 10 years. Moreover, previous generations of secular and progressive women who hadn't been schooled past age 12 and had children as teenagers, prioritised education – not sport – as their daughters’ tickets out of a pugnacious state. “(The parents) say, ‘Education is the only thing we care about,’” says Sirwan Sami, the former head of the Nowruz Cycling Club, which formed outside Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan. “(Others) say if (the women cyclists) fall over and die, it's God's will... honour is more important.” Sami added that when girls joined his team, their families usually asked him to protect the girls’ reputations above all else. “The pro female cyclists on far-off roads outside the capital cities often experience shou ing and jeers, although men generally stop short of knocking off the pro women from their bicycles.”

While the USA went from hunting down Saddam, encouraging regime change and enforcing American democracy on a reluctant and quickly fractionalising populace, the women’s Al-Shaab Team formed by Ayad and Alatar found its first coach, Mahmoud Ahmed Fulayih. He saw bigger things on the horizon: men and women’s national teams, junior development and even the Olympics. “I was out at Al-Shaab club, and coach said, ‘You want to race?’ and I said, ‘Sure.’ I fin- ished first,” Ayad said. “I was hooked. And so was Shura.”

But as elections loomed, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a once hard-drinking, womanising Jordanian street criminal radicalised in a Jordanian prison, descended on the beleaguered country with Al-Qaeda in Iraq. The terrorist group began a campaign of kil ing prominent sports figures, including the entire Davis Cup tennis team, professional footballers, Olympians, and anyone who dared compete in sport in public. In early December 2006, Al-Qaeda kidnapped Fulayih at his home at gunpoint – days after he had led the men’s team in its first successful Asian Games in Doha, Qatar – and killed him. Authorities found his body in the desert two days later. “A lot of sports women and coaches, they killed, just training in the road. But he was the first one to really believe in us and he became a martyr for it,” saiys Ayad, barely able to hold back tears 20 years later. “My cycling days at university and competing were the happiest days of my life. And after our coach died, I left cycling. I was too sad and my family was afraid for me.

“Of course, we thought about leaving. Shura’s family went to Jordan. We wanted to go to the States, but they didn’t accept the visa,” Ayad says. “We didn’t want to end up in a refugee camp, so we stayed.” But no sport, including cycling, could outrun the insurgents. Everything went underground.

While the Baghdad team recovered, other groups around mostly Kurdish Iraq, including the Nowruz Cycling Club, the Shabab Club, the Kahraba Club, and the Nasiriyah Club, started to develop organically. Liberal men began to encourage women to get on their cycles again, creating divisions joined to their clubs. Female cyclists started travelling regionally to compete under the Iraqi national flag again. But beyond the Kurdistan region, one ugly beast, Al-Qaeda, was defeated only as another one, Da’ash, or ISIS, reared its ugly head. “They just basically changed t-shirts,” said Ahmed Albasheer, an Iraqi comic. Still, as the Bush administration literally compared Iraqi regime change to taking the “training wheels” off a bike, Ayad and Alatar, who returned from Jordan, married, raised children in Baghdad and restarted their involvement in the national cycling association.

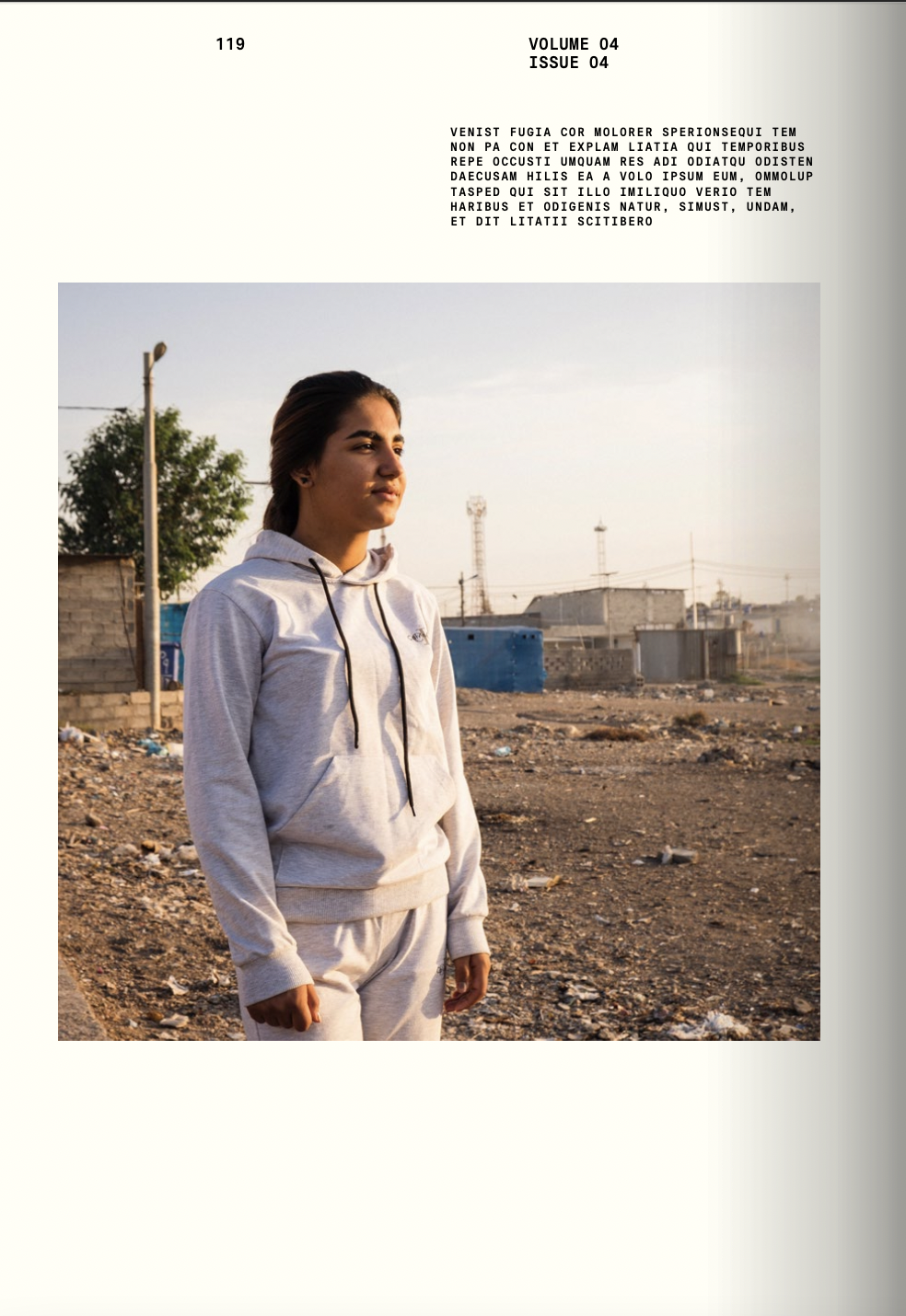

By that time, Sozi Dilshad, a cyclist from Sulaimaniyah in the Newroz Cycling Club, had already brought home a cluster of medals and trophies from regional competitions. “When I ride my bike I feel like I’m in a different world,” Dilshad told The Independent newspaper in 2015. “In a race, the only thing I am thinking about is getting to the finish line. We have to really focus, which requires energy, and we get very tired – but at the same time, the focus means I am not thinking about problems in my own life.” Dilshad had to convince both her father and her mother to continue, as all were torn about Da’ash and the economic strife the group caused. “As a female cyclist, the best thing is to have a degree and then you can be a representative for your country, go abroad and have an impact,” Dilshad says.

But Ayad and Alatar were already at work. The two successfully petitioned the Iraqi Cycling Association to form a wom- en’s professional team, in addition to fos- tering youth development. Both agreed to take unpaid positions as coordinators, thus handling all the training, entry forms, travel and support for the national team, as well as grassroots support for the up-and-coming junior cyclists. “My dream, in fact, is many things because Iraq is not perfect yet. I hope one day it will be alongside the developed countries and pay more attention to women’s sports,” says Laynah Hadi, one of the young prospects in Basmiyah City last February.

Today the national team is six women strong, and in three years, the cycling association has helped form seven women’s teams competing around the country, including in the annual Iraqi Road Cycling Championship in Erbil. And while the national team has yet to medal at the Asian Games – the regional qualifying event for the Olympic Games – it has remained competitive against the better-funded teams from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. One cyclist, Duaa Abbas Rukabi, has gone to the USA to train and compete on the criterium circuit. She was primed to take her first podium in May 2024 before a crash took her off course for a few months. Her previous best result had been 13th place in the Arab Road Cycling Championships in 2022. “I love that cycling is individual, but it’s also a team sport where we work together and support each other’s goals,” said Rukabi, a former mountaineer, from her training base in Texas. “But the Iraqi federation doesn’t support women’s cycling. I myself was promised an Asian participation – a Continental team involvement – and ended up getting nothing. I would say they are unreliable.

“We need to focus on the women’s team, and an overall strategic plan to develop the women’s team alongside financial support.”

Ayad and Alatar don’t disagree: “The men get the money from the government and they make a lot of races for them – boys from Iraq are very good – and just a trickle goes down to us,” Ayad said. “If given the support, we could be at the top; right now we have a very good team with potential.”

A new guard has rolled into the Iraqi Olympic Committee promising more attenion to its cyclists, however. Aqeel Meften, an Iraqi lawyer, owner and founder of the Iraqi Union Bank and now the committee’s ninth President participated in a race on International Cycling Day and made this statement afterward: “The Olympic Committee are determined to return the sport of high achievement to its rightful status after a long slumber.”

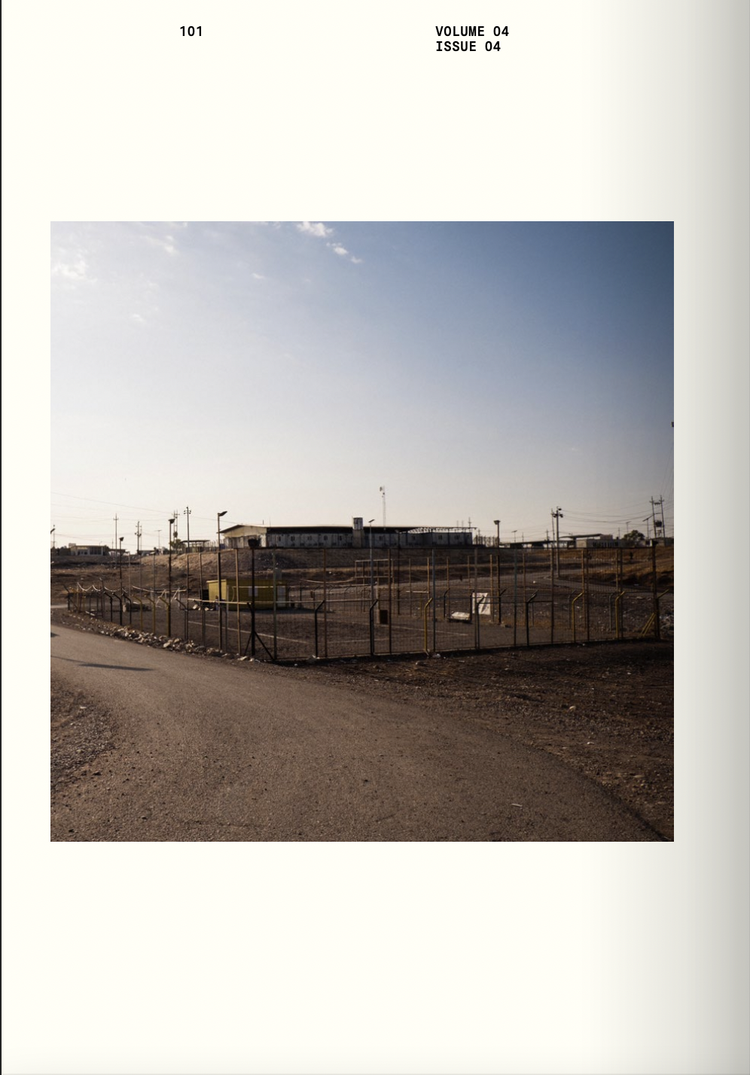

Cycling still has a long way to go, how- ever, especially in Baghdad, especially for women. City engineers, cyclists and envi- ronmentalists have complained about the complete lack of cycle lanes in the country. In order to train, clubs have to bus their teams far outside cities where threats of un- hinged drivers or hiding insurgents loom constantly. The government has a former football stadium – whose architect was Le Corbusier, no less – that could possibly lend itself perfectly to a track. Moreover, Iraq – ranked last on the Global Environmental Performance Index for its car pollution – is just not healthy for cycling lungs.

But Ayed and Alatar are not deterred, not even in the face of the USA’s newest as- sault on Iran. The region is again unstable and planned races face cancellation, includ- ing an August road race in Sulymaniyah and the Erbil competition. The Tour de France Femmes remains an even more far-away possibility. Yet, as every good freewheeler knows, slow and steady wins the race – with a touch of oomph toward the end. “I like cycling; I like my life in it,” Ayad says. “Now we have gone from nothing to something. We make races; we clear roads; we have a team. We are crossing barrier by barrier to now make our dreams a reality.”