WHY YOU SHOULD CARE

Because sometimes it’s about more than just putting one foot in front of the other.

By Adrian Brune

THE DAILY DOSE, APR 08 2018

The sun had just started to rise on the waterfront of Lagos, Nigeria, as the crowd of runners turned onto the Third Mainland Bridge — the second-longest bridge in Africa. I checked my watch: nine-minute miles. Not bad. I settled into my marathon pace and the more than 6 miles ahead of me to Lagos Island, the commercial hub of the city.

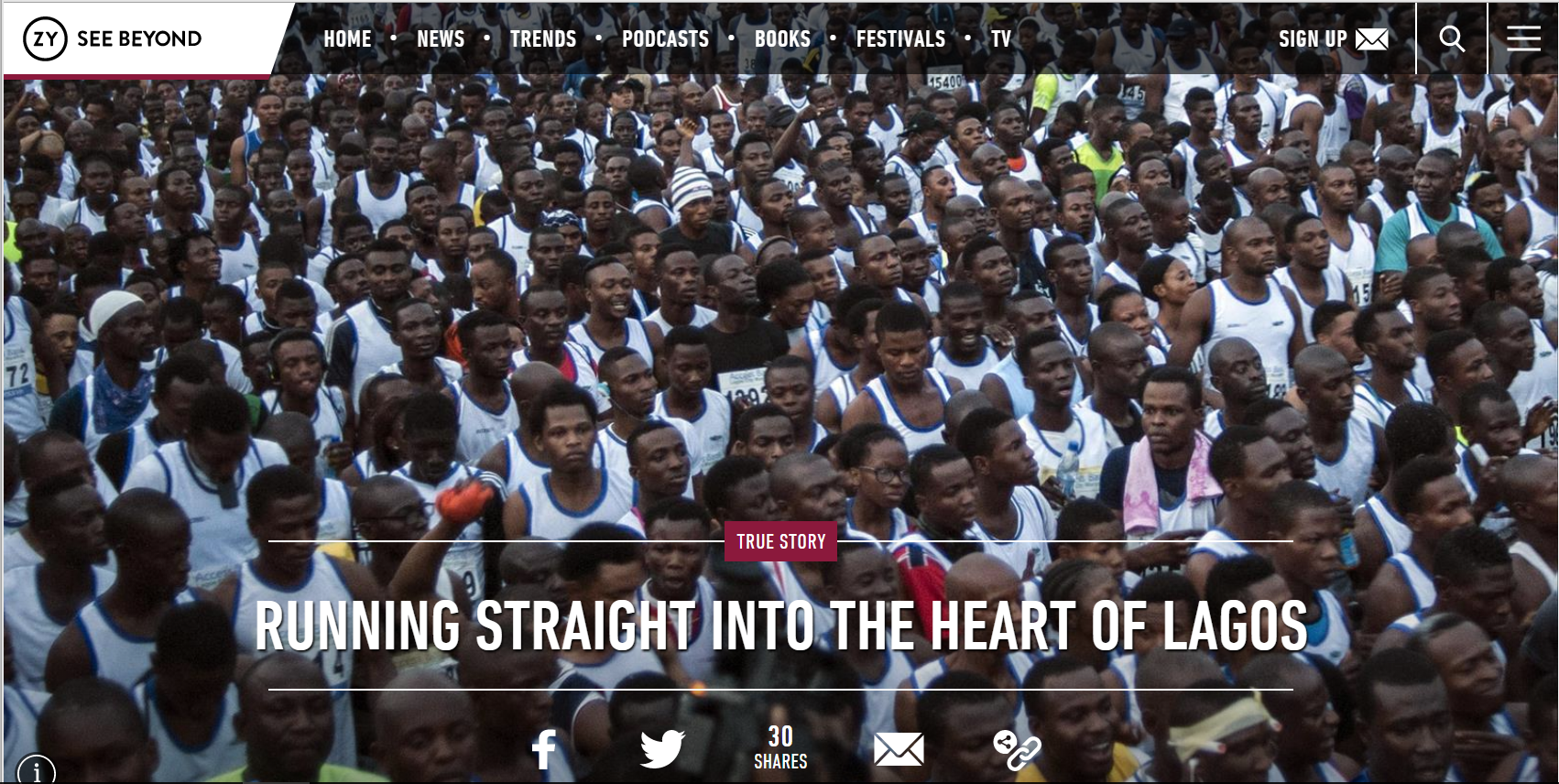

It had been a harried morning already. The third edition of the Access Bank Lagos City Marathon had started in the wee hours at the National Stadium in the Surulere district, and it had not set off on solid footing. With a truck blocking the highway to the start line, runners had less than 10 minutes to warm up before the gun — and I was nearly run over trying to snap a few photos of them taking off.

Still, nothing so far had made me question my decision to come and run this marathon — not the heat, not the crowd, not the warnings about the crime, the corruption, the mass discontent of the population — until the Third Mainland Bridge. To the left of me as I started my ascent, I saw oil refineries smack-dab in Lagos Harbor; to the right, I looked over the slums of Iwaya and Makoko, with thousands of wood-and-tin shacks built on stilts just above the slick, oily water. Black smoke from cooking fires burned my eyes and my throat as I watched children in dugout canoes fish for the market or their daily meal. Only then, as I struggled to run while inhaling smog — the smell of diesel was everywhere — did I start to wonder: What had I gotten myself into?

Moreover, which comes first in the developing world? Development, or a marathon that is designed to inspire the populace to develop? Before Lagos, I had run marathons all over the Middle East — in Irbil, Iraq, in Palestine, in Amman, Jordan, and in Beirut, which was still rebuilding after the decades-long civil war. But until Lagos, I never questioned whether a city was ready to host a marathon.

Currently housing the largest metropolitan population in Africa at more than 20 million people, Lagos is made up of three islands and a mainland of 285 square miles that harbors some of the worst traffic in the world. There are no zoning laws in Lagos, and since the 1970s, the city has been overrun by the oil and gas industry, which rules corrupt soldiers, politicians and police through the power of the greased palm. Former “estates,” or planned residential neighborhoods, are overgrown with roadside markets, and informal settlements of people with nowhere else to go use the city waterways and side streets as toilets and refuse dumps.

Before I left, a friend who had visited Lagos on business called it the “Devil’s Playground” for all its abject poverty and the corruption that led to the abject poverty. Other friends warned me about the petty theft, owing to that poverty and joblessness, that characterized parts of the city. When young boys ran too close to me and eyed my iPod, I grew fearful — it might have been a dumb idea to bring it, but I needed music and I wanted to give the city its fair due.

But my impression of Lagos started to change significantly as I, and possibly 30,000 other runners, started running down the Third Mainland’s off-ramp and onto Lagos Island, the once bustling city center with half-abandoned skyscrapers, colonial-era British slave jails, stadiums on permanent permit hold and a coterie of broken-down yellow minicabs. Somewhere along the bridge, I had picked up a running buddy, a 25-year-old named Godwin, who stopped when I needed water, shared my melted Kind bars brought from the States and told me he thought he could “make it to the medal.

Participants in the 2017 Access Bank Lagos City Marathon on Feb. 11, 2017. SOURCE PIUS UTOMI EKPEI/GETTY

Medals were one of the things that kept the focus of the people who signed up for the marathon — a tangible item possibly worth a couple of bucks on the street or to hang in a room, offering some sense of accomplishment. The other sensation the marathon offered was transcendence. I saw it on the faces of the men and women who took selfies at the half-marathon mark, heard it in the cheers of the uniformed schoolgirls on the side of the road and read it on the marathon ads lining the streets of the route. Bromides such as “Access the Life” and “Beat the Odds” proved one thing: The Access Bank Lagos City Marathon had its advertising down cold.

The organization of the race proved a bit more laissez-faire. In addition to the marathon, the sponsors decided to put on a 10K race, which put the total at 100,000 “athletes battling for the various prize monies,” according to one local newspaper’s account. It was more like 100,000 hot, sweaty, sun-exhausted people, including me, run-walking past the posh compounds of Ikoyi and Victoria Island to duke it out for finishers’ refreshments and that hard-sought medal. By the time I crossed the line at 5 hours, 15 minutes, the water and the medals were gone. I was too jet-lagged and exhausted to care.

Others were a bit more vocal: “Where is the water? Where are the medals?” asked Efe Pote from Namibia in the British-inflected accent common in East African countries. “These conditions were like I had never experienced before. I want a medal. I need a water.”

I finally received a chair backstage about the time a fight broke out over a chest of icy bottles, just as Lagos’ state governor, Akinwunmi Ambode, presented an 18 million naira ($50,000) check to Abraham Kiprotich, a Kenyan-born French marathoner who won the men’s race in 2:13:04, and one to Alemenesh Herpha Guta, an Ethiopian who won the women’s race in 2:38:25.

Halfway through the hard part. SOURCE: COURTESY OF ADRIAN BRUNE

Ambode repeated a claim I had heard at the press conference: The Lagos City Marathon would have a “Gold Label” certification from the sport’s governing body, the International Association of Athletics Federation, “within two years.” He added with the Nigerian pride to which I was growing accustomed: “We are tired of foreigners, most especially Kenyans, coming to win this marathon. We need … to give the Kenyans a run for their money.”

I wound up staying an additional seven days past the marathon. I was trying to square the things I had experienced with the billboards around the city adorned with the Access Bank mascot encouraging Lagosians to “Keep on Running” for 2019. The Lagos marathon and the governorate had to make huge strides to attain its “gold” standard in 10 years, much less two. Before anything else, it needed to improve the lives of the populace — the people whom the marathon supposedly benefited — the Godwins running beside me, the schoolgirls cheering me on, those dwelling in the slums and breathing in the smog of international corporate neglect. In The Economist’s annual Global Livability Rankings, Lagos rated as the second-worst city to live in behind Damascus, Syria. But I was invited back for next year, and I’ll go. I’ll likely run again. If for nothing else than to see how many miles the city has come.