WHY YOU SHOULD CARE

Because sports revolutions often precede social reforms.

By Adrian Brune

THE DAILY DOSE, AUG 01 2017

Motivation in sports occasionally can come from unexpected places. Consider Ons Jabeur, 22, a Muslim tennis player from Tunisia. Ranked No. 103 by the Women’s Tennis Association, she improbably found herself up a set on No. 6 Dominika Cibulkova in the second round of this year’s French Open. As Jabeur waited for her Slovakian opponent to serve, the soundtrack playing in her head belonged to … Eminem. “It depends on where I am in the match,” Jabeur tells OZY. “Sometimes ‘Beautiful,’ sometimes ‘One Shot’ helps me through.”

The unlikely mental boost from the Detroit rapper helped Jabeur surge to a 6-4, 6-3 victory over Cibulkova, her first against a top-10 player. As Jabeur hoisted the Tunisian flag for all to see at Roland Garros Stadium in Paris, the moment belonged to her country — and to Arab women around the world.

Jabeur is in the vanguard of a trailblazing quartet of Islamic players from the Middle East and North Africa who are popularizing tennis in a region where for centuries Muslim women have had to be content with playing indoor sports while sequestered from the world. Along with Jabeur, three other pros — Cagla Buyukakcay (WTA ranking, No. 158) and Ipek Soylu (No. 162), both from Turkey, and Fatma al-Nabhani (No. 473), from Oman — are trying to level the playing fields for women.

Tournaments in Qatar, Dubai, Morocco and elsewhere also have helped to increase the profile of tennis in Islamic states. Only the 26-year-old Buyukakcay, though, has come out on top in the region’s competitions, winning the Istanbul Cup in 2016. Increasingly, Islamic players are questioning why more women like them aren’t in the draws and are challenging tournament directors to start investing some of the purse money, which usually goes to foreign players, into junior programs for young women with dreams of pursuing professional tennis.

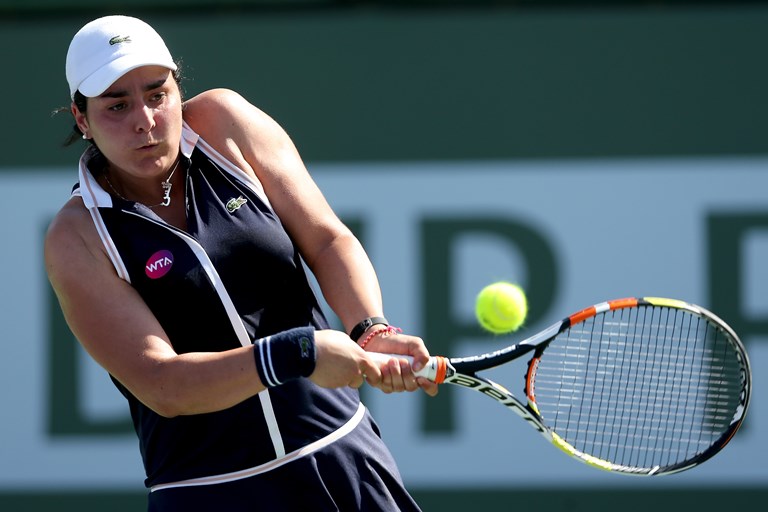

Ons Jabeur of Tunisia bears down at the 2015 BNP Paribas Open in Indian Wells, California.SOURCE MATTHEW STOCKMAN/GETTY

Prize money for women tennis players totaled $120 million in 2014, with a mere 1 percent of players pocketing 51 percent of those purses. Yet Middle Eastern players, many of whom are not among the ultra-rich, press on even as the cost of competing on the professional circuit hits about $160,000 per year. “As Arab women, we need to know that nothing is beyond our reach,” says al-Nabhani, 26, who lives and trains at home in Muscat. “Whether it is running a 10K or winning a Grand Slam, it is important we know that we can aim and achieve the highest honors. Things are changing rapidly in the Arab world, and it is time for us to ride the wave and grab the opportunities.”

Al-Nabhani rose through the junior ranks by practicing with her brothers. The reverent yet headstrong Omani wears a custom-made Nike kit, a three-quarter-sleeve top and leggings beneath her skirt. On court, she’s often seen looking for a nod of approval from her mother and coach, Hadia Mohammed, who always wears a black hijab and an abaya. Off the court, she speaks candidly about her situation, which is similar to that of other Islamic players. “It was a huge challenge being the only [woman] in the fray and doing something that hasn’t ever been heard of before in the region,” al-Nabhani says. “But I followed my passion and looked up to my brothers, who were competing. If my brothers were not there, I don’t know where I would have been.”

As a pro, al-Nabhani has so far notched four singles titles and four doubles titles on the WTA tour, in addition to competing for Oman in the 2016 Rio Olympics. But she’s still gunning for a Grand Slam appearance. Her older brother, Khalid, attributes the delay in part to a dearth of Gulf money for player development. “One of the biggest challenges is getting [sports officials] who see player development as a burden to understand that having world-ranked local players is very important for making the game popular within the country,” the elder al-Nabhani says. “I believe if the resourcesare available, [Fatma] is capable of reaching the top 100.”

Oman’s Fatma al-Nabhani at the Dubai WTA Open in 2012. SOURCE STR/GETTY

That lofty perch has been within reach of Buyukakcay and Soylu, 21, who were the first Turkish women to compete in the main draw of a Grand Slam. (Both declined to comment for this article.) At the moment, only three spots separate Jabeur from becoming the first Middle Eastern woman to crack the top 100 in a generation. She kicked off the year by reaching the third round of the Australian Open, followed by a third-round appearance in the French Open. During the Wimbledon qualifiers, she beat No. 17 Asia Muhammad of the U.S. to make the main draw, but bowed out in the opening round. The Tunisian is ready to wrap up the year’s Grand Slam circuit by making a “good impression at the U.S. Open,” practicing at home when “it’s very hot so I can get used to the weather in New York.”

In June, Jabeur, who also grew up in a tennis family and competed in the 2012 and 2016 Olympics, was one of 12 players to receive a $50,000 grant from the ITF Grand Slam Development Fund, which aims to alleviate the competition costs of up-and-coming players and slot them in Grand Slam draws. “It’s one of the reasons why I’m winning matches,” Jabeur says. “It’s allowing me to relax a bit, have fun and play better.”

But not completely. Not until she channels Eminem all the way to a Grand Slam trophy. “Tunisia is a very small country, and when someone is doing well, you cannot just say you are playing for yourself,” she says. “We have a lot of successful women in Tunisia, and for me it’s an honor to be one of them and to encourage other women to believe in themselves.”