Restorative Arts

Tears, Folds, Grime Disappear From Vintage Posters

February 16, 2006|By ADRIAN BRUNE; SPECIAL TO THE COURANT

Josephine Baker came to Lee Milazzo in tatters.

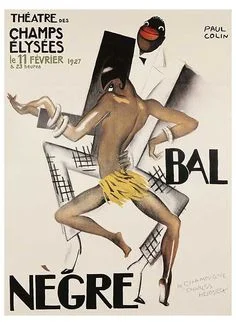

But despite torn corners and fold marks, Baker's beauty still radiated from the poster, beckoning people to join her for her show at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees in February 1927.

So Milazzo, a vintage-poster restorer and gallery owner, took Baker's delicate likeness into his Stamford shop, Poster Conservation. After a long bath, some reconstructive surgery around the edges and a new linen bodice, the famous entertainer took center stage again.

``You don't see many of these,'' said Milazzo, pulling the restored Paul Colin-designed ``Bal Negre'' poster out of its drying rack. ``These posters were never meant to last; they were printed on the cheapest paper possible so they wouldn't. But at least this one will be around a few more years for a few more people to enjoy.''

From the absinthe-drinking, fast-living late-1800s through the early years of the Cold War, posters were everywhere: Colorful bottles of Campari lined Italian city streets; Cunard cruise ships invited people on ``votre route sur l'Atlantique'' from the subways of New York; and ``Le Gorille et la Femme'' lured people into the Casino de Paris to see a show featuring a woman and a gorilla.

In recent years, many of these vintage advertisements have started showing up in shopping-mall poster shops, on restaurant walls and for sale on the Internet. Most look perfect because they are reproductions; many originals that look just as good were once as tattered as the Baker poster.

Poster restoration is an art form in itself, but no design school teaches it, and only a handful of people practice it around theworld. Some, like Milazzo and Joshua Tangeman of New York's J. Fields Gallery, got into it by chance -- Milazzo while attending Parsons School of Design in New York (he left school to start his business), and Tangeman after a stint at Rhode Island School of Design.

Now that vintage posters have emerged from attics and thrift shops, restorers have become almost as sought-after as the art.

On a recent Saturday afternoon in his studio, filled with paper, dilapidated posters, drying posters, brushes and lots of glue, Tangeman rolled a coat of wheat paste onto a large piece of light-cotton canvas, applied a sheet of acid-free paper and pasted onto that a poster for ``Tiko and the Shark,'' a 1964 Italian B-movie. Back and forth, back and forth for about 20 minutes, he rubbed out any air bubbles.

The process, known as linen-backing, dates from the turn of the century but re-emerged within the last 20 years. Collectors, who recognized the posters' aesthetic work and who wanted to preserve them, would glue them to large pieces of cotton gauze or canvas, or even silk.

Vintage posters now come to restorers in a variety of conditions, meaning the restoration can range from a quick washing to a piecing together of large chunks of a torn poster like a mosaic, filling in gaps with bits of colored paper from unsalvageable ones.

``We recently had a relatively rare [Leonetto] Cappiello Absinthe poster which we probably shouldn't have started, because it was dry-mounted and very damaged as well,'' said Ian Wright of M&W Graphics, a restoration studio a few blocks from the J. Fields Gallery in Chelsea. ``And the worst-case scenario happened. ... It shattered into tiny bits.

``We actually put it back together like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle,'' he said, adding that most conservationists and galleries don't recommend that much restoration.

Tangeman and Wright learned poster restoration from Larry Toth, the original owner of J. Fields and the man many credit as the pioneer of modern restoration. Toth established J. Fields in 1979 and began using a heavier weight canvas backing that soon became a standard in the industry. Dealers appreciated its durability because they could roll, ship and shuffle the old posters from show to show with minimal damage. Picture framers valued it, too, because the poster no longer would ripple with the first change in humidity.

Vintage poster collecting began in Europe then migrated to the East Coast during the late 1970s, Tangeman said. ``Posters were the poor man's art. People could afford them back then,'' he said.

Somehow, images meant to sell products to the masses took on a certain individuality in their second lives as decorations.

``Posters show a sense of someone's mentality, whether they enjoy cooking, or they've visited a certain place or they're from a certain place,'' said Mickey Ross, the owner of the Ross Group, a poster gallery in Westport. ``Just today I had a customer whose husband worked in the oil industry. I showed her several old ones in that field, one for Priceless Oil and one for Shell.

``Some people collect military posters, some railroad, some aviation. What a nice way to use an interest, as the launching point for a poster collection,'' he said.

At the Chisholm Gallery in New York, ardent collectors can find originals by famed poster artist Adolphe Mouron Cassandre -- but none for less than $20,000.

Although Cassandre had no reverence for his work -- ``A poster ... is meant to be a mass-produced object existing in thousands of copies, like a fountain-pen or automobile,'' he said -- many collectors do today.

One of the pioneers of modern poster design, Cassandre came to Paris in 1915 to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, then the Academie Julian. Needing to earn extra money, the Ukraine-born artist took a job at a printing house. Forty years earlier, French printmaker Jules Cheret had invented the ``three stone lithographic process,'' which allowed artists to attain most colors with three stones -- usually red, yellow and blue -- and transformed European cities into vast street galleries and heralding the start of modern advertising.

Cassandre drew his first ad for a cabinetmaker, Au Bucheron (The Woodcutter), and took first prize at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs. With that ad and that award, Cassandre launched his own agency, Alliance Graphique, and revolutionized the printmaking industry with acclaimed posters for Vin Nicolas and Nord Express that were inspired, respectively, by the cubism of Picasso and the surrealism of Magritte.

``We just rehung the gallery, and now have a wall of Cassandre pieces, some extraordinary Cassandre -- `Le Jour,' for example, one he designed for a French newspaper from 1933,'' Gail Chisholm said. ``It's one of only two known examples in the world.''

Many critics consider Cassandre's prints legendary, but during a time of industrial, political and social revolutions, there was plenty of work to go around. While the First World War loomed, across the ocean in America, printmakers, including James Montgomery Flagg, thrived on propaganda art. After World War I, the French ruled supreme again with Art Deco, showcased at Paris' Decorative Arts Exposition of 1925, where simplified and streamlined shapes governed and sleek, angular letterforms ruled.

Although he worked for others besides his occasional lover and lifelong friend, Josephine Baker, collectors agree that French lithographer Paul Colin created some of his best designs when inspired by his muse, and the work lives on in places as far from Paris as Connecticut.