Two Slaves' Escape Stories, In (mostly)their Own Words

January 27, 2008|By ADRIAN BRUNE; Special to the Courant

Adrian Brune is a free-lance writer in Brooklyn, N.Y.

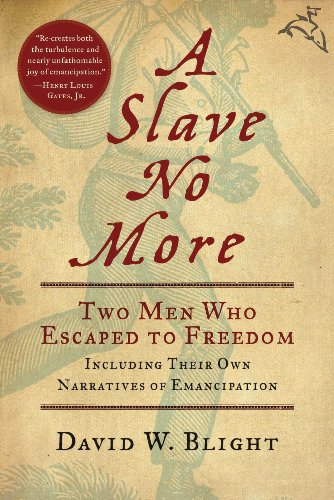

A SLAVE NO MORE: TWO MEN WHO ESCAPED TO FREEDOM

by David W. Blight (Harcourt, 397 pp., $25)

The antebellum and postbellum periods of American history have inspired hundreds of significant works of literature on the horrors of slavery and the Civil War, but none more poignant than those produced by the victims of the "peculiar institution" - slaves themselves.

Frederick Douglass wrote one of the first harrowing slave narratives in 1845, followed by Sojourner Truth in 1850 and, 11 years later, by Harriet Jacobs, whose "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl" for the very first time detailed slaves' sexual abuse. These books helped their authors, especially Douglass, achieve fame and a place in history, but hundreds of fellow freedmen also penned their plights and went unpublished.

Though fewer than a dozen slave narratives are thought to exist, in 2003 historian David Blight came across two: that of John Washington, an escaped slave from southern Virginia, and Wallace Turnage, a slave who ran away five times before gaining safety with Union troops in Alabama.

Blight, director of Yale University's Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition, took these hand-written accounts, given to him by their authors' relatives and friends and wove them into an engaging, provocative book, "A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom."

The book has an unusual format. In the first part, Blight tells the slaves' stories for them, providing details about their circumstances for context. While slave narratives usually end with the gaining of freedom, Blight, through historical documents gathered from descendants, attempts to recreate the men's post-emancipation lives in the second segment. The last section presents Washington and Turnage's stories in their own words, nearly verbatim.

As he notes in the first sentence of his narrative, Washington (1838-1918) was born into slavery in Virginia, the son of a white man he never knew. He spent his early years on a plantation, before his mother was sold to a Fredericksburg socialite in the 1840s.

After his master leased his mother and his four half-siblings to another planter - and Washington became a houseman - he developed a fierce determination to escape. Taking advantage of the Union occupation near Fredericksburg in April 1862, he crossed the Rappahannock River and found freedom in the army camps, eventually working as cook for Gen. Rufus King.

Experiencing more hardship, Turnage and his family were shipped from North Carolina to Alabama where he was sold as a field hand. After fleeing four times - and enduring harsh beatings upon his return - he made a dramatic final escape for a Union stronghold after hiding in a swamp for a week, dodging Rebel troops.

"Now when I got down [to the water] I seen a little boat. . . . It stood like it was held by an invisible hand; so I got in the little boat and it held me," he wrote. A few hours later, as a storm approached, Union soldiers pulled him aboard their gunboat.

Turnage went on to work for an officer in the Third Maryland Cavalry and then as a glass blower, watchman and waiter in New York, burying two wives and raising several children.

Washington worked in Washington as a house painter, eventually retiring to Cohasset, Mass., where one of his five sons was a railroad signal operator.

Sometimes grammatically challenging, their stories are nonetheless the most compelling aspect of "A Slave No More," though Blight retells them well. He adds little-known facts, such as Lincoln's meeting with black leaders, including Douglass, to ask for their endorsement of a plan to re-colonize the freed slaves in Africa. But he crosses into perilous territory when he speculates on their lives as free men, at points over-dramatizing.

That aside, the dearth of slave narratives and this testimony of overwhelming desire for freedom make the book a powerful addition to the black history library.