Iraqi Perspectives On War

May 29, 2008|By ADRIAN BRUNE; Special To The Courant

As a Navy lieutenant serving a one-year tour, Christopher Brownfield formed his own impressions of the war in Iraq. When he returned home to New Haven last year, he brought back Iraqi impressions of the war. He brought home Iraqi art.

In doing so, Brownfield became an accidental curator to an exhibit of 75 Iraqi sculptures, drawings, paintings and photographs showing at the Pomegranate Gallery in New York through June 21.

"Oil on Landscape: Art from Wartime Contemporaries of Baghdad" is the first major U.S. exhibition focused entirely on Iraqi art since the 2003 invasion.

"Americans might consider these works to be politically charged, but it's important for Americans to think about this from an Iraqi perspective," Brownfield said. "These canvases reflect Iraqi views on "Shock and Awe," suicide bombing and a homeland torn apart by bickering parliamentarians.

"To these artists, that's not politics - that's everyday life," Brownfield said.

When the "Shock and Awe" campaign to remove Saddam Hussein from power began, most Americans saw the unfolding events through remote, fuzzy television images of lights flashing and soldiers rushing the capital city.

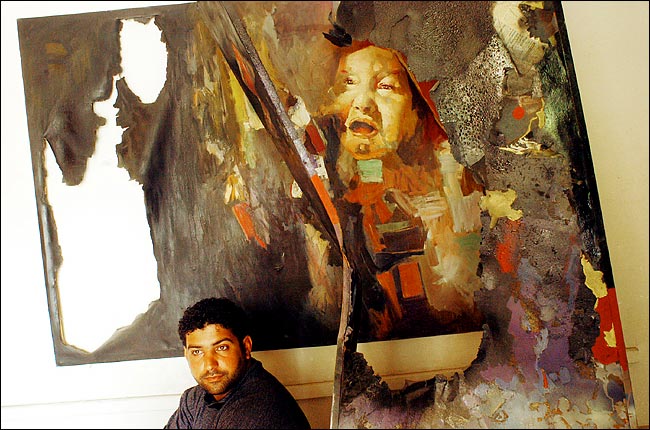

Mohammed al-Hamadany painted an Iraqi perspective of that night: an installment of 25 color paintings depicting the abstract faces of anxious Iraqis peering through the windows of their homes, the Iraqi flag stained with oily handprints, decapitated women and empty, toppled ladders.

A chance occurrence led Brownfield to the artwork of al-Hamadany and the others in the show. When a State Department official invited him to dinner at the compound of Ahmed Chalabi, Brownfield went searching for a tie to wear with this borrowed suit. On his search, he hit up all the usual piecemeal all-purpose Iraqi stores, containing "everything from hooka pipes to Persian rugs to toothpaste," Brownfield said. But "about three layers in a particular one, and beyond the stereotypical Orientalist painting," Brownfield said he found original art that "aimed to send a message.

"I realized these artists had seriously studied art - that it hadn't just been a passing interest or a quick way to make money," he said. The officer eventually came across more work, met a few of the artists' friends and intermediaries, and opened up a clandestine exchange in which they brought more provocative works, and he passed on much-needed money as well as books on Western art.

Until now, artists in Iraq's capital city have remained a cloistered collective, keeping their pointed works in the back rooms of shops around the Green Zone and leaving the world at large without an indigenous perspective of the campaign.

Though Brownfield's collection largely focuses on post-invasion work, he also included art that represents Iraqi life before 2003. Besides the 5- by 2-foot "Shock and Awe" paintings he hand-carried through customs at Kennedy International Airport (to questioning by many officials), Brownfield brought back photo-realistic drawings of Iraqi people by Sadik Jaffar, who uses a "nom de guerre" meaning "one who sees the truth" (to protect himself from reprisals); metaphorical paintings of broken power lines created by As'aad al-Saghir; and Ahmed Nousaife's abstract depictions of Mesopotamia in more idealistic times.

Brownfield wrote and published a 70-page exhibit catalog, which features all of the artists' work, providing context and their connections to the insurgency. "Mohammed said a few weeks ago he felt as if he finally had 'a window to the outside world' - that now there's hope and a reason to keep creating," Brownfield said. "We found a place where they could renew the vitality of their work." Because of security concerns, the artists declined comment.

Initially, Brownfield bought the art for himself, but on his return to the U.S., he came across Oded Halahmy, an Iraqi ex-patriate, sculptor and owner of the Pomegranate Gallery in Manhattan's SoHo district, and the two discussed the possibility of a show.

"Chris' efforts, bringing these works to the U.S., completely related to our vision," said Halahmy, who opened the gallery a few years ago to introduce people to the artistic endeavors taking place in the Middle East and whose own abstract sculptures have appeared in the Guggenheim, the Hirschhorn and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. He said, "Baghdad has historically been viewed as the cultural capital of the Middle East and primary innovator in the fine arts. Chris has helped demonstrate that these artists can create something out of the destruction."

The show has already received significant attention, and Brownfield plans to sell the most works, though he might keep a few of Jaffar's drawings. The gallery and Brownfield will distribute all the proceeds directly to the Iraqi artists, most of whom are unemployed and rely on artwork sales to feed their families. He doesn't plan any other similar show, hoping instead to find "foundations to carry the torch.

"These artists experienced things that would have torn them apart if they hadn't expressed them. But artists like Mohammed saw the possibility of sending their work abroad. He said, 'This is my one shot to send the world my message.' "