Nick Bollettieri, dans son académie à Bradenton en Floride en 2022 (© Art Seitz)

A HUCKSTER WHO KNEW NOTHING ABOUT TENNIS REINVENTED TENNIS TRAINING

There comes a point about seven minutes into the 2018 Showtime documentary, Love Means Zero, when the often-smug, yet never-say-die tennis coach Nick Bollettieri — sitting amid the ruins of the Colony Beach and Tennis Resort in Sarasota, Florida — explained the relentlessness of his pursuit. “My father said: ‘If you ain’t nobody, ain’t nobody gonna to talk about you.’”

It was possibly a strange thing for an esteemed tennis coach to say, a man who earned a spot in the International Tennis Hall of Fame without ever playing a professional tennis match. But if anything, Bollettieri, who died on Sunday, December 4, 2022 at the age of 91, craved attention — and fame. His throughway came via the children of the rich and the otherwise preoccupied elites of Gulf Coast Florida.

“I did things nobody thought of. I broke the rules of taking kids away from their parents, and brought them to an academy – the first one in the world. If I didn’t break those rules, I don’t believe tennis would be where it is today“, he says, naming the pros who came through the Colony and then the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy during the 80s and 90s: Andre Agassi, Monica Seles, Jim Courier, Aaron Krickstein, Mary Pierce. “Come on, let’s keep going baby! My Serena, my Venus, Anna Kournikova, Maria Sharapova, Tommy Haas… if you take all the students, I think there’s about 180 grand slam high notes…”

“Baby, I don’t know half of what most coaches know about pronation, turning hips and shoulders, the dynamics of the stroke, centrifugal force. Shit, I don’t know any of that.”

“All I know is that I wanted to be a winner and with winners.”

At age 12, I wanted to be a winner, too. Sitting in my bedroom in Tulsa, Oklahoma following a day of private school, a tennis lesson and/or a drilling session, plus a fitness routine, then dinner, homework and 60 pushups before bed, I would read Tennis Magazine — then the only American tennis publication left standing — where Bollettieri was the “instruction editor” and absorb his bits of advice for my game. “Hit and exaggerate the follow through“, Nick would advise on my backhand. “Wrap that racquet around the opposite shoulder at the end, baby“, he would tell me on my forehand. I volleyed from the forehand with two hands so I would turn my body appropriately, “to direct the oncoming ball without increasing the power.”

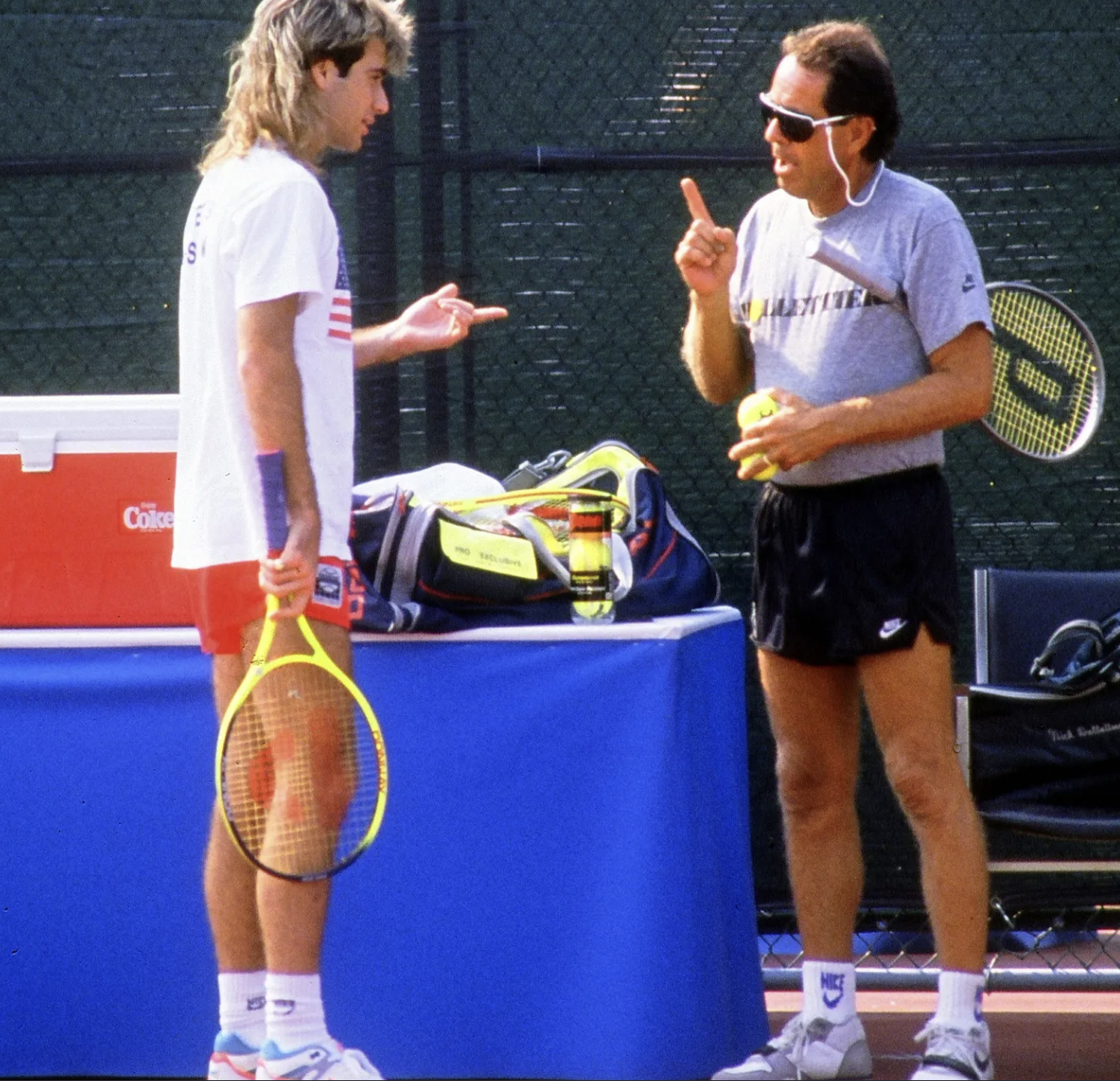

Andre Agassi et Nick Bollettieri (© Art Seitz)

By the time I was 16 and Jennifer Capriati was 16, however, I knew that I would never have the moxie or the makings of a pro player. The best I could hope for was a practice spot on a university tennis team, which I gained for a year in 1994. But, Nick… Nick kept on going.

Born and raised in Pelham, New York, to Italian parents, Nick Bollettieri played football at Pelham Memorial High School and attended Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, where he first picked up a tennis racquet. Dodging the Korean War, Bollettieri nevertheless enlisted in the U.S. Army’s 187th Airborne Division. “The paratroopers were a volunteer division services. Why did I want to do that?, Bollettieri said in a 2015 motivational speeches. I wanted to be with a group that expected nothing else but the best.” Still he flunked the exam for the Naval Air Corps, but acceded to the advice of his father and enrolled in law school at the Univeristy of Miami in 1956 and kept a side job as a tennis instructor on the North Miami Beach tennis courts for $1.50 an hour. Bollettieri often came to law classes donning his tennis gear, to which the dean replied that he should “come dressed as a lawyer“, until his last day when he said “Dean, I have a few words for you.” After he handed over his books, Bollettieri said, “this is not for me.” Afterward, he called his father and told him he “would be one of the best coaches in the world.” His father replied, according to Bollettieri, “Son I will support you in everything you do, but you are responsible for the result.”

All it took was one kid — that’s all Bollettieri needed. Some may have thought Jimmy Arias with his windshield-wiper, wide-Western forehand would have propelled the 47-year-old to tour fame. But it was Brian Gottfried, a skinny Jewish kid born in Baltimore, Maryland who landed on Bollettieri’s courts in the mid-1960s that helped launch the coach’s career. Bollettieri took his protégé all over the Southeast to play tournaments, to find better players from whom he could learn and to land on courts where Bollettieri could teach his brand of motivation. “Tales of the militaristic nature of life at Nick’s academy abound. I know that turns many people off, wrote Peter Bodo for Tennis Magazine. The way I see it, Nick’s borderline harsh, discipline-based program brought something new to the soft and — let’s face it — bourgeoise sport of tennis. And the espirit d’corps he instilled in so many players, for so many years, played an enormous part in their success.”

Gottfried was Bollettieri’s start. While he was ascending to No. 3 in the world, Bollettieri started to bulid his empire. First, at the prestigious Port Washington (N.Y.) Tennis Academy, a northern tennis factory that counts Vitas Gerulaitis and John McEnroe as its prized students. Then, in 1978 Murf Klauber of the The Colony Beach Hotel and Tennis Resort hired Bollettieri as its director of tennis. He got busy recruiting, bringing in a core group of students from around the country: Anne White, Jimmy Arias and Kathleen Horvath and Carling Bassett soon joined.

Anna Kournikova, âgée de 10 ou 11 ans, avec Nick et Nick Bollettieri (© Art Seitz)

Bollettieri financed his school with the sons and daughters of the bourgiousie, who stayed at the Colony, while his better, scholarship players lived at Bollettieri’s house, where, in exchange for cleaning floors with tooth brushes and picking up cigarette butts around the hotel, among other things, they learned the Bollettieri way. When his growing cadre of students outgrew Bollettieri and a good friend, Mike DePalmer Jr., bought a tennis club on 75th Street in Bradenton and a motel to house them.

Luck struck twice when Andre Agassi, another rebellious child of immigrants, landed on one of Bollettieri’s Palm-tree lined courts in 1983. After seeing Agassi play for 30 minutes, legend has it that Bollettieri tore up the check Agassi’s father gave him for three months’ room and board — all the Agassi family could afford. By that time, Prince and Head racquets had come calling and Bollettieri had moved from the Colony to a 40-acre former tomato lot in nearby Bradenton. Nike came calling next, and the rest is a reflection in Bollettieri’s oversize Oakleys. Despite eight marriages, estranged children, financial boom-and-busts and a few grudges held by a few of his former protegees, including Agassi, Bollettieri, at age 86, hardly acknowledged the wreckage, even when it surrounded him in Love Means Zero.

By 2004, the Colony Beach and Tennis Resort was in financial trouble and no number of new owners could save it from abandonment, squatters, teenage graffiti taggers and finally, the wrecking ball in 2018. I saw it first hand, by then a 42-year-old journalist and aging player who climbed over the fence after a match at the nearby Longboat Key Tennis Center. I would take photos and write an essay about Bollettieri’s last days at the Colony and the sale of his academy to the sports agency, IMG — the closest I ever got to Nick’s secret sauce. The great still turned up at the occasional Slams and in instruction videos for the International Tennis Hall of Fame, which inducted him in 2014, but wasn’t as omnipresent as he once was. “God and a few of the mafia gave a message to get Nick in“, Bollettieri jokes on camera. But being there is one thing: it’s my obligation to help people to get to another level of play.” Still, “being there” might rank as the Bollettieri’s life achievement — his own defiant “f-you” to anyone who ever told him “no.”

Nick Bollettieri, entouré notamment de Jelena Jankovic (deuxième en partant de la gauche), Tatiana Golovin et Andreï Medvedev (les deux à droite), © Art Seitz

Some wondered if Nick Bollettieri might ever die — his energy endless, his skin seemingly incapable of decay. “If you look at Nick’s history, Nick does not look back, I just go forward, he says in Love Means Zero. I want to come across loud and clear. I did not think about things. I did not think of the ramifications, whether negative or positive, or neutral… I’ve never thought about being loved. What I think about: ‘Did I help you in life, did I give you a direction? ”

“Sometimes, a person may not love you, but if you’ve made an impact on your life, that’s success, too.”

But by August 2021, Bollettieri was in hospice care, mostly bedridden. Tommy Haas flew in from New York to see him, and Gottfried, Arias, Anne White, Robert Seguso, Carling Bassett-Seguso, Dick Vitale, and even Agassi, the player who shunned him for years, were in contact. Bollettieri even autographed racquets for charity events he would never attend.

Upon word of his passing, the tributes came rolling in over Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Even in his afterlife, however, Bollettieri just moved on, unapologetic for anything. On his official Instagram page, the announcement of his passing was one quote: “The mindset of champions is very simple. I don’t accept second place.”

IN THE NEW ISSUE:

Roger Federer, l’héritage invisible (the invisible legacy) | Charles Haroche, Frédéric Vallois

De la fleur au fusil... (From flower to fun) | Rémi Bourrières

Humilité (Humility) | Myriam Bouguerne

Pure Aero : une raquette qui fait effet (a racquet that works) | Mathieu Canac

Entretenir la machine (Maintain the machine) | Thomas Gayet