Prince Charles buys a copy of The Big Issue from a vendor, 1998.

No British institution does pomp better than Buckingham Palace, but the House of Lords comes close. Its gold-plated doors are opened by members in tuxes and tails every day. Of all the lords who huff and puff and blow hard in its stately halls, however, the one least expected there—Sir John Bird, whose story has echoes of The Pursuit of Happyness in its sheer unlikeliness—treats the place like his personal digs.

Born in a Notting Hill slum, Bird became homeless at age 5 (“My mum and dad didn’t recognize the rent man. He was not more important than cigarettes and drink,” he says), and he was in and out of juvenile-detention centers starting at the age of 12. He learned reading and printmaking in prison.

“This screw [guard] came in one day and asked me if I wanted a book,” Bird, 75, who wears a blue pin-striped suit, black shirt and tie, well-worn Doc Martens, a Royal Society for the Protection of Birds lapel pin, and a day’s worth of stubble, says. “I must’ve paused, and he said, ‘Oh, you can’t read, can you?’ I’d never, ever admitted to anybody that I’d been through Roman Catholic school and learned all about Jesus and everything, but that I was pretending I could read.”

Sir John Bird, who became homeless at age five, in Notting Hill.

Bird also started drawing and painting, and eventually won a scholarship to the Chelsea College of Art and Design. But not long after, he went on the lam from the police—once more due to petty theft—and escaped to Scotland, where he started sleeping rough again.

On the streets of Edinburgh, Bird’s fortune changed when he met Gordon Roddick, the soon-to-be husband of Body Shop founder Anita Roddick. “In 1991, Gordon was in New York and saw a copy of Street News and thought [it] was brilliant,” Bird says of the street newspaper sold by homeless people in New York starting in 1989. Roddick was inspired to start something similar in the U.K. and tapped Bird to help found and run it. They called it The Big Issue.

“He ultimately asked me to help because I had been a rough sleeper and a street drinker and had been in and out of prisons and homelessness,” Bird says. “And he said, ‘You know, you’re like these people … and you are not sentimental about the poor.’”

The Early Days

Since The Big Issue’s launch, in the early 90s, big-name Hollywood actors, including the press-shy Benedict Cumberbatch and Michael Sheen, have endorsed the publication or signed up as ambassadors, as have a number of politicians—Ed Miliband and David Lammy—and perhaps their most famous satirist, Armando Iannucci. The man who considers himself a “working-class Tory” has published exclusives from J. K. Rowling and talked the Archbishop of Canterbury into giving street sales a try.

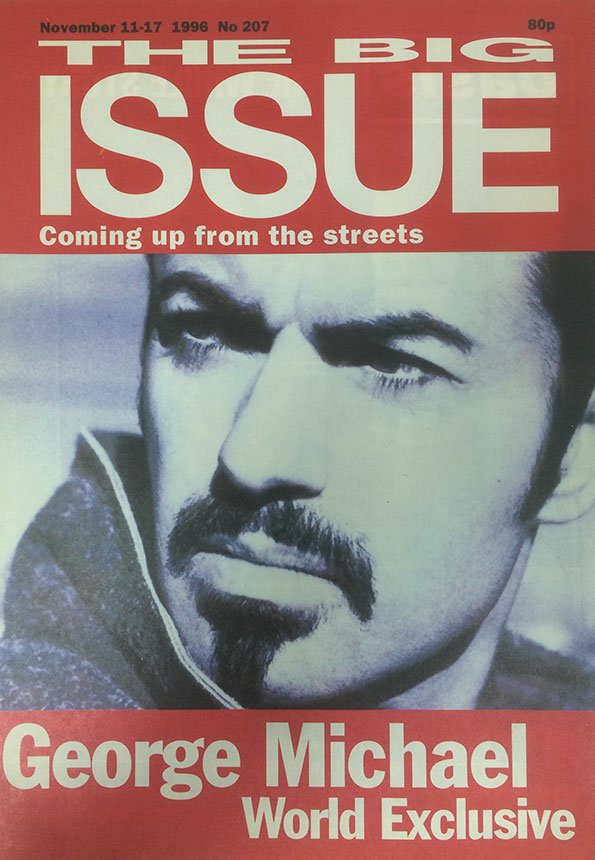

George Michael graces the cover of The Big Issue, November 1996.

When pop star George Michael had to reckon with his penchant for public sex in Hampstead Heath, he went to The Big Issue with the story. “I did not know the music of George Michael. I probably still don’t,” Bird says. “But I knew he had had a public struggle and was trying to cope with some of the ‘shit’ that people I knew were coping with—sex, drugs, mental health. So George seemed a natural fit with The Big Issue—people winning control of demons.”

When Michael appeared on the November 11, 1996, cover of The Big Issue, “we not only sold more copies, we helped increase the reputation for a place where honesty and integrity were the hallmark of our journalism,” Bird says. “Increasingly vendors were seen as holders of news that was worth having.”

The Big Issue had arrived.

“George [Michael] seemed a natural fit with The Big Issue—people winning control of demons.”

Since then, the Glasgow-based editorial staff of about 15 people has put out an issue every week for its vendors to sell. Today, Bird sells the paper to poor and homeless vendors for £1.50 (about $2). They then sell it to the public for £3 ($3.99) and pocket the profits.

After 20 or so years as editor of The Big Issue, in 2013 Bird awoke in the middle of the night in a crisis of conscience. “I realized that the reason people were saying that John Bird and his ilk were good at thinking outside the box was because the box wasn’t working,” he says. “And the box was Parliament.”

So he applied for a position as a life peer in the House of Lords, a seat appointed by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister, in lieu of acquiring one the old-fashioned way: inheriting it. “I’ve never been a form filler, and I’ve never been good at interviews. It took about two years to get in, and then they rang me and said, ‘Congratulations, John Bird, you are now Lord Bird of Notting Hill.’”

Selling The Big Issue on the streets of London.

Bird has since become the lords’ go-to guy for poverty schemes and initiatives. He also happens to be the best thing going at local galleries. “He’s a bit like my old boss, Roger Daltrey,” says Ruth Law, Bird’s right-hand woman, who worked for the singer-songwriter and patron of the Teenage Cancer Trust before arriving at The Big Issue four years ago. “He’s very plainspoken, very down to earth, and not afraid to tell it like it is.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, Bird engineered The Big Issue to come “full circle in about two years,” says Paul McNamee, the magazine’s Glasgow-based editor, converting it from a street publication that dealt in cash to the digital world. When the first U.K. lockdown shut down street vendors, The Big Issue made subscriptions available online, with proceeds going to the out-of-work vendors.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the founding of the publication, which has just undergone a complete redesign by Matt Willey, currently the art director of The New York Times Magazine. McNamee excitedly describes it as “a bit of the Esquire of the 60s, Time Out of the 70s, some grit, more classic features, and maximizing the great content that we have online.”

Back in the House of Lords …

Bird chats with people here and there as he leads me onto the outdoor terrace of the House of Lords, where a sticky toffee pudding awaits him, and continues with his discourse on the issue nearest to his heart: the homeless.

“Most of the other lords are angled toward giving the poor relief, holding their hand, helping to sustain them, and few pieces of legislation are actually geared toward moving people out of poverty,” says Bird. His dedication to The Big Issue illustrates a different approach to tackling the problem: giving people jobs.

Bird, left, Gordon Roddick, right, and members of the Big Issue staff at the newspaper’s launch, 1991.

Today, Bird is preparing for an address requesting £360 million (nearly $409 million) for rent arrears that he will soon deliver to the Lords Chamber. “Because I had been poor and I’d got out, I don’t look at the poor as another species,” he tells me. “If they are another species, then I have just managed to leap the species gap.”

The time for the speech arrives. Bird’s legislative aides rise from their chairs and make eyes toward the gilded chamber doors—their signal for Lord Bird to quit chatting. Shortly after, Bird appears on the floor, asking that his fellow lords take note of the combined impact of the end of pandemic aid and the rising cost of heating due to new environmental regulations as, “and I am sorry to use the cliché that everybody talks about … a perfect storm for hundreds of thousands—millions—of people who are caught in this kind of trap.”

For 15 minutes, Bird speaks about the never-ending cycle of poverty in the U.K., the importance of investing in social education, government tokenism, and how Winston Churchill had to “borrow the future—an enormous amount of the future—to defeat the Nazis.... We cannot poodle around with poverty.”

Bird listens to another hour of mumbled responses from his contemporaries before ending in scratch-your-back flair. “When I saw [Prime Minister Boris] Johnson immediately after he got elected, he came and he put his arms around me … and he said, ‘Thank you, John, for the job.’

“I said, ‘Do me a favor.... Remember the homeless.’ … He owes me, and I’m calling it in.”

Adrian Brune is a London-based journalist

To support The Big Issue, you can buy a copy of the magazine from your local London vendor, buy a subscription (vendors receive 50 percent of the net profits), or make a donation to the Big Issue Foundation